A lot has been said and written about Israel and the Palestinians, not in the least since Hamas attacked Israel on October 7, 2023. Emotions run sky high, and polarize the whole world. One often is either 100% for Israel, or 100% for Palestinians. Or, as the detractors would say: one either supports genocidal land grabbing colonizers, or one supports bloodthirsty child murdering terrorists.

If you have been a regular reader of my articles, you know that I abhor jumping into the fray like that. Much better to stop, take a step back, and to look closer at history as a first starting point. Not parts of history, carefully selected, but as much of it as possible. Only then does a much more nuanced view present itself. In this case, not a pleasant one. One that likely will upset both sides, to various degrees. So, here we go...

As a father, I had to step in countless times when my boys were fighting. “Well, HE started it!” “No, liar! YOU did! You did this FIRST!” “Well, only because you had done that before!” You all know how this goes. An endless back-and-forth, impossible to sort out, unless you go way, way back.

So, where to begin?

A very long time ago. Let’s look at the first mentions of Israel and Palestine, for starters.

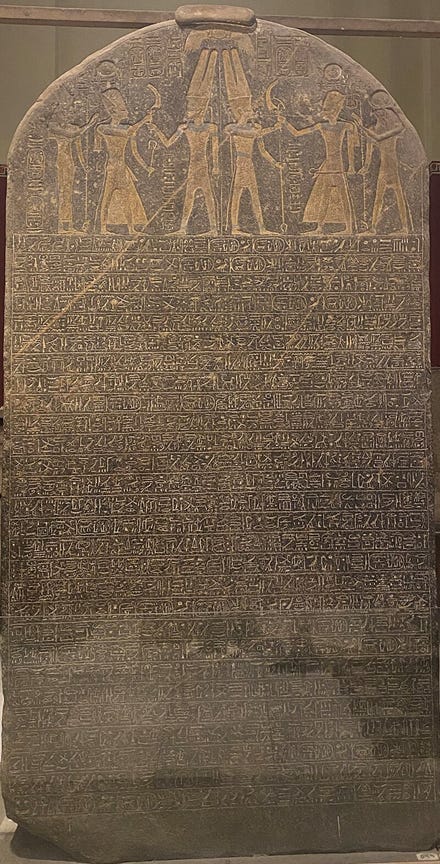

The first mention of Israel found to date is the Merneptah Stele.

This stone slab is the Victory Stele of pharaoh Merneptah, who reigned in ancient Egypt from 1213 to 1203 BCE, as the fourth Pharaoh of the 19th Dynasty, and son of Ramesses II, also known as Ramesses the Great. The stele was found in 1896 by famed Egyptologist Flinders Petrie in the royal city of Thebes. On it, several military campaigns of Merneptah are detailed. The bulk is about a campaign against invaders from Libya, in the West, when their king had allied with several northern peoples and attacked. At the end of the text, however, attention shifts to Canaan, likely because some of those cities had revolted, seeing their chance in the chaos of that war, and the fact that most of the Egyptian army was deployed against the Libyan king in the west.

“[…] All the rulers are prostate, saying «Peace!»,

not one among the Nine Bows dare raise his head.

Plundered is Tehenu (Lybia), Hatti (the Hittites) is at peace,

Carried off is Canaan with every evil.

Brought away is Ascalon, taken is Gezer,

Yenoʿam is reduced to non-existence;

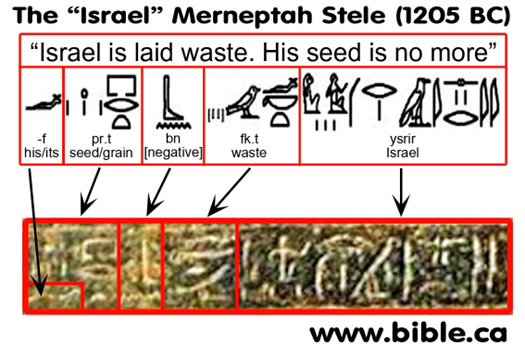

Israel is laid waste, having no seed,

Khurru (Syria) has become widowed because of Nile-land.

All lands together are (now) at peace,

and everyone who roamed about has been subdued,

- by the King of S & N Egypt, Baienre Meriamun, Son of Re,

Merenptah, given life like Re daily.”

ISRAEL is mentioned! Laid to waste, ‘having no seed’. This reference sparked a lot of debate, because people asked: why mention Israel if it is just a band of wandering tribes, nomads, barely arrived and settled in Cana?

Some scholars objected to this interpretation, and pointed out that the name ‘Israel’ on the stele is followed by the determinative for ‘people’, and not for city or nation.

“William G. Dever opposes the revisionists/minimalists, defending that the Israelites from the Merneptah’s stele should be understood as an ethnic group, distinct socio-economically and politically from the Canaanites, known as such by the Egyptian intelligence, sufficiently numerous and well established in the central hill country to be perceived as a threat by the Egyptians, although not organized into city-states.” (Alexandru Mihăilă, “Ethnicity in Early Israel. Some Remarks on Merneptah's Stele,” in Anuarul Facultăţii de Teologie Ortodoxă „Patriarhul Justinian” anul universitar 2009-2010, University of Bucharest.)

That being said, the reference “Israel is laid waste, having no seed” is interpreted as the fact that Egypt destroyed the grain storage of the people of Israel, which meant they were condemned to famine the next year, which erased their existence as a military threat. The mention of grain led some researchers to suggest that "Israel functioned as an agriculturally based or sedentary socioethnic entity in the late 13th century BCE" (Hasel, Michael G. (1994), "Israel in the Merneptah Stela", BASOR, 296 (12): 54, 56).

The (re-)discovery of a fragment of a pedestal in the storerooms of the Egyptian Museum of Berlin changes the above academic discussion on the exact meaning of ‘Israel’ on the Merneptah Stele. On this fragment 3 name-rings are visible, with the first two reading Ashkelon, the second Canaan, and the third (partially preserved) reads Israel. Orthography suggests a time mid-18th Dynasty! This indicates the presence of a recognizable people named Israel, before Ramesses II and before his son, Merneptah. Peter van der Veen and other researchers extensively studied this fragment, and concluded that their findings “indeed suggest that Proto-Israelites had migrated to Canaan sometime during the middle of the second millennium BCE.” (Veen, Peter van der, Christoffer Theis, and Manfred Görg, 2010 Israel in Canaan (Long) Before Pharaoh Merenptah? A Fresh Look at Berlin Statue Pedestal Relief 21687. Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections Vol. 2:4, 2010 | 15–25.)

Either way, this presents irrefutable proof that links a distinct group of people, whether or not organized in cities or kingdoms, but were called ‘Israel’, in that strip of land often referred to as Canaan, more precisely in the hill country of central Canaan. They were there 3000 to 3500 years ago. That is a fact of history, undeniably so.

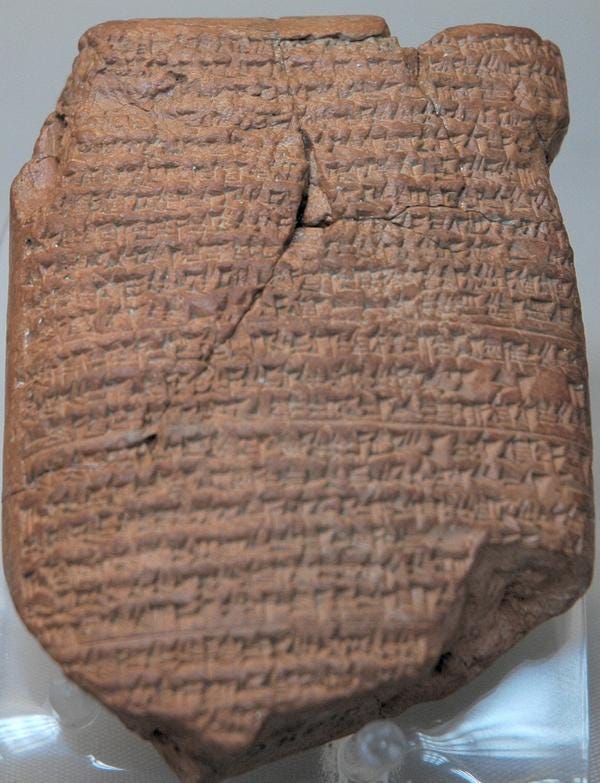

From that point on, there is more and more archaeological proof that seems to support the Biblical accounts, that the Israelites indeed lived in the central hills of Canaan, where Jerusalem was, and from there established an expanding kingdom, under kings such as David, Solomon, and their successors. The Biblical story is corroborated many times over, for example this link with 2 Kings 24 (At that time the officers of Nebuchadnezzar king of Babylon advanced on Jerusalem and laid siege to it, and Nebuchadnezzar himself came up to the city while his officers were besieging it. Jehoiachin king of Judah, his mother, his attendants, his nobles and his officials all surrendered to him.

In the eighth year of the reign of the king of Babylon, he took Jehoiachin prisoner.) and Jeremiah 52.

(Chronicle Concerning the Early Years of Nebuchadnezzar II, ca. 590 b.C.)

This is how the Babylonians themselves recorded this event, on the above cuneiform tablet: “In the seventh year [598/597], the month of Kislîmu, the king of Akkad mustered his troops, marched to the Hatti-land, and besieged the city of Judah and on the second day of the month of Addarunote he seized the city and captured the king.”

(The difference in reckoning, 7th or 8th year, can simply be explained through a difference in counting: do you start counting with full years only? Or do you count the partial first year as a year, as well?)

The whole episode as described in the books of Maccabees chronicles how Israel fought against the Hellenizing influence of the Seleucid empire, founded in 312 b.C. by Seleucus I Nicator, one of the generals of Alexander the Great, after Alexander’s death. This fight shows a very tenacious will to survive, a very strong sense of identity, and the willingness to die to preserve that identity.

The claims of ‘Israel’ or ‘Judah’ to those lands ends in the first centuries a.D., when yet another revolt against their overlords, this time the Romans (against whom they had revolted from the moment Rome had taken over the remnants of the Seleucid empire in 64 a.D.), is the last straw.

A first war, between 66 and 73 a.D., led to the destruction of Jerusalem and the temple, as well as the dispersion of many Jews throughout the Roman empire. Continued unrest, including a massive uprising during the Kitos War that consisted of a series of local uprisings of Jews against the Romans, ended with the Bar Kochba revolt, crushed by emperor Hadrian himself in 132 a.D. The result: large scale massacre against the main Jewish households remaining in Israel, basically depopulating the whole of Judea. The Roman historian Cassius Dio wrote "50 of the Jews most important outposts and 985 of their most famous villages were razed to the ground. 580,000 men were slain in the various raids and battles, and the number of those that perished by famine, disease and fire was past finding out, thus nearly the whole of Judaea was made desolate." This seems confirmed by archaeology.

After this, Israel only existed as a dream of lost glory in the hearts and minds of the Jews in the diaspora.

One important element: after crushing the Bar Kochba revolt, Rome changed the name of the province from Judaea to Syria Palestina, and they rebuilt Jerusalem as a Graeco-Roman city under the name of Aelia Capitolina. A typical claim is that this was done out of spite, and to fully sever any link between the Jews and Judea, their homeland. Others contradict that, and point out that Herodotus, already in the 5th century b.C., called this area Συρίη ἡ Παλαιστίνη, romanized: Suríē hē Palaistínē, or Syria Palestina.

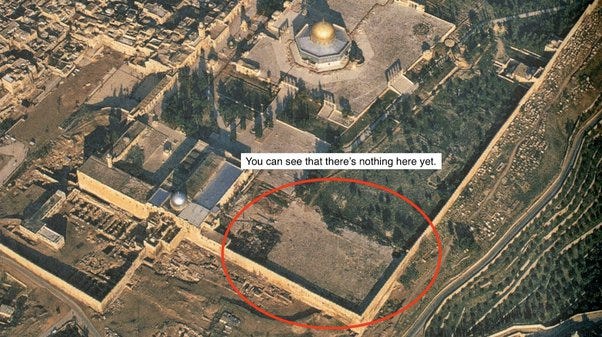

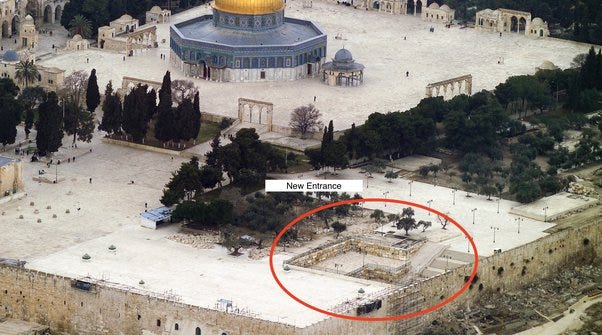

I need to make one more point: archaeology is politics. So today, people deny that there ever was a Jewish presence in Jerusalem or the Holy Land, that there was no Jewish Temple on the Temple Mount (I’ll come back to that later, in detail). In 1999, the Waqf (Islamic organization in charge of the Temple Mount) started construction work, and went in with bulldozers, removing tons of soil, without any regards for the archaeology. Even in the face of outcry by secular and worldwide archaeologists, not just from Israelis themselves, the Waqf and Jordanian authorities refused to have any dirt dug up at the Temple Mount analyzed in situ.

5 years later, a crew of volunteers then decided to sift through the dirt after it had been deposited in heaps outside the Temple Mount. In it, they found millions of archaeological traces. “Seligman said that the IAA has been examining the dumped remains, primarily pottery sherds, coins and even some nails. About 40 to 45 percent dates to the Byzantine (fourth to seventh century A.D.) and early Islamic (seventh to eighth century A.D.) periods; about two percent dates to the late First Temple period (seventh to sixth century B.C.)—"The background noise of Jerusalem archaeology," in Seligman's words.” (Source)

(Image source)

NBC reported on this, and quoted the director of the Waqf: “I have seen no evidence of a temple,” said the Waqf’s director, Adnan Husseini. He had heard “stories,” he acknowledged, “but these are an attempt to change the situation here today, and any change would be very dangerous.” Incredible words: ‘change is dangerous’, bypassing the fact that it is THEY who are trying to change the facts, through their destructive revisionism.

Israeli Historian Gershom Gorenberg cynicaly but astutely remarked: “Dig a centimeter beneath the debate over antiquities and you hit the debate over whom the Mount belongs to, and a centimeter beneath that is the war over whom the entire country belongs to.”

Sifting through the rubble from the Mount, incontrovertible proof of that ancient Jewish presence has been found, sadly completely out of context.

High Priest Golden Bell – In the same excavation at the drainage tunnel by Eli Shukrun, a golden bell was found dating to the Second Temple period. There is no precedent for this artifact from any excavation in Israel. Our only knowledge of such an object is from the biblical description of the bells sewn to the garment worn by the high priest (Ex. 28:33-34).

The Imer Seal Impression is the most direct evidence found. “The seal bears the inscription: “(Belonging to) […]lyahu (son of) Immer”. The Immer family was a well-known priestly family at the end of the First Temple period, around the 7th – 6th Centuries BCE. Pashhur son of Imer is mentioned in the Bible as “Chief officer in the house of God” (Jer. 20:1)” (Source)

Archaeologically, there is ample support for this history of Israel.

With this, we now need to talk about the origin of Palestine.

The oldest mention of Palestine is from Ramesses III, successor to Merneptah. On his mortuary temple in Medinet Habu, in Thebes, he mentioned military successes against the ‘plst’, as one of the ‘sea peoples’ (alongside the Tjeker, Shekelesh, Denyen, and Weshesh), defeated in a sea and land battle around 1175 b.C. The name plst corresponds to what we know as the ‘philistines’, as mentioned in the Bible, famously as the people who battled with king Saul, challenging them to fight their champion Goliath. Goliath was then slain by a young David, who would later succeed king Saul.

Who were those philistines? Their earliest archaeology places them at the coast of Canaan. This supports their origin from the Aegean region (Greek), and their material culture further shows this. Their earliest pottery, for example, is Mycenaean (Late Helladic) IIIC pottery. An article from SOTS about the Philistines mentions this: “The Old Testament is more specific, claiming several times that the Philistines came from Caphtor (Jer 47:4; Amos 9:7; compare Gen 10:14 [according to some translations]; Deut 2:23), which is widely believed to denote Crete, the inhabitants of which were called Keftiu by the ancient Egyptians. Note, for example, that the kilted Keftiu depicted bearing tribute in the Egyptian tomb of the vizier Rekhmire in Thebes (ca. 1450 BCE) strongly resemble the Cretans represented in the palace of Knossos in Crete. Again, in the anti-Philistine oracles in Ezek 25:16 and Zeph 2:5, they are called Cherethites (Cretans).”

It shouldn’t be a surprise, then, to see how Herodotus, a Greek himself, remembers these people with their Greek name, and names that region Syria Palestina, in the 5th century b.C. This older mention by Herodotus does not refute any claim that Hadrian officially renamed that territory from Judaea to Palestina to sever the link of the Iudaei, the Jews, with that territory completely, it only shows where that inspiration came from, and where Hadrian was definitely adding insult to injury by renaming the Jewish homeland after their old arch-nemesis, the Philistines.

The Philistines, as Aegean invaders, occupied the fertile plains of the Canaanite coast, centered around 5 main cities, as mentioned in the Bible: Ashdod, Ashkelon, Gaza, Ekron, and Gath. SOTS makes this observation: “The fact that part of the Promised Land remained in the hands of the Philistines is “anticipated” in Noah’s blessing of Japheth (ancestor of the Mediterranean races) in Gen 9:27, “May God make space for Japheth, and let him live in the tents of Shem,” Shem as its ancestor symbolizing Israel.”

From the earliest mention by Ramesses III on, the Philistines, just as Israel, appear in the chronicles of all the other peoples in the Ancient Near East. The Assyrian king Tiglath-pileser III (745-727 b.C.) conquers the remaining city-states of the Philistines, and forces them to pay regular tribute. SOTS concludes: “Prophetic oracles exult in the fall of the Philistines (Jer 47:4-7; Ezek 25:15-17; Zeph 2:4-7; Zech 9:5-7). After the exile the Philistines gradually lost their separate identity as a people, something that was complete by the end of the 5th century BCE.” Only the name remained, and the memory among the Greeks that a part of their people went and settle there, to be rekindled officially by the Romans in 132 a.D., but without any corresponding Philistine or Palestinian ‘people’.

From 132 a.D. on, there is no trace of either Israel or Palestina as an independent state, or even as a ‘people’. With the exception of the Jews. Theirs is a very unique story.

Normally, looking at history, when a people is kicked out of their homeland, and forced into exile, they either silently disappear from History, they merge with another nation, or they reinvent themselves into a new people. Typically within 4 generations, any remaining link is fully severed, as no one is left who has a first hand memory of the original country, and the importance of the stories and memories is lost. Look at this very curious fact: Judaism stated that the Holy Land never lost that status of being promised to them, and the Jews themselves actively kept that idea alive. You see already in the 10th century mentions of ‘Next year in Jerusalem’ (in this case a poem by Joseph Ibn Abitur called ‘A'amir Mistatter’), and in the 15th century Jews wrote a book detailing the Minhaggim, or traditions, of various Ashkenazi groups in Europe, explaining how the Passover prayers included that phrase, as a heartfelt prayer and wish: may we celebrate the Passover next year in Jerusalem.

L'Shana Haba'ah B'Yerushalayim.

לשנה הבאה בירושלים

What incredible tenacity and vision!

An important element to note, is that Judaea/Palestina was in effect depopulated in 132 a.D. That means that there are no Judaeans (Jews) nor any ‘Palestinians’ left in that area. Jewish/Roman historian Josephus talks about 1.1 million civilians who died after the fall of Jerusalem (Josephus explains this number: “the greater part of whom were indeed of the same nation [with the citizens of Jerusalem], but not belonging to the city itself; for they were come up from all the country to the feast of unleavened bread, and were on a sudden shut up by an army” [The Wars of the Jews, Book 6, chapter 9]) , and Roman historian Tacitus cites 600,000 inhabitants of Jerusalem (Historiae, Book V, chapter 19). Those who survived were either sold into slavery (Josephus mentions 97,000 captives), or fled. A very small number remained, in the various villages in the countryside.

Yet while there are ample sources showing how the Jews maintained their identity, even in exile, during the course of centuries and millennia (which is truly unique), there are, as far as I know, exactly zero sources that talk about ‘Palestinians’ in any sort of exile. Later sources might talk about Palestinians, but simply to denote ‘those who live in Palestina’. Which would be, at such dates, a mix of Arabs, Christians from all over Christendom who settled after a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, Jews who came back or descendants of the very few survivors, nomadic people from that region, and perhaps a mix of any of the other peoples displaced by the events that took place at the collapse of the Roman Empire, both the Western part and later the Eastern part of it. Not denoting a ‘people’ with their own culture and heritage, but simply to show where they lived. In all that time, from 132 on until 1948, Palestina, if named such, was only a province of a larger entity, be it Byzantine, the Caliphate, Crusader kingdoms or Mongols, Mamluks, followed by the Ottomans and finally the British.

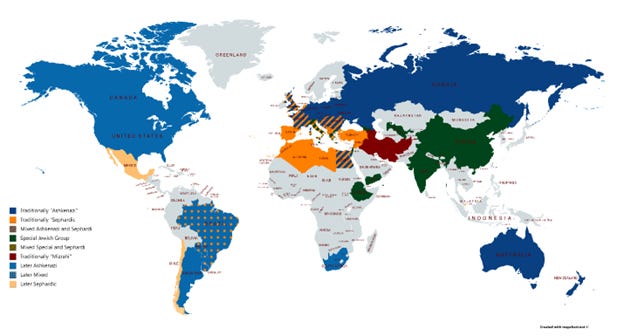

That brings us to this realization: there is no Palestinian ‘people’ in the period between 132 and 1948 we can follow, but there IS a Jewish people, albeit not a unified and monolithic block. Among the Jews, there are several ethnic groups that can be discerned, all resulting from wave after wave of exile and diaspora, as seen on the below map:

Color legend, in descending order: Traditionally “Ashkenazi”; Traditionally “Sephardi”; Mixed Ashkenazi and Sephardi; Special Jewish Group; Mixed Special and Sephardi; Traditionally “Mizrahi”; Later Ashkenazi; Later Mixed; Later Sephardic

Despite the at time enormous differences in cultural and physical appearance of those groups, recent genetic studies show a generally strong relation to each other. See Hammer MF, et al. (June 2000). "Jewish and Middle Eastern non-Jewish populations share a common pool of Y-chromosome biallelic haplotypes". This study concludes: “The results support the hypothesis that the paternal gene pools of Jewish communities from Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East descended from a common Middle Eastern ancestral population, and suggest that most Jewish communities have remained relatively isolated from neighboring non-Jewish communities during and after the Diaspora.”

In the roughly 2000 years since the end of Judaea in 132 a.D., the surviving Jews have been subjected to oppression after oppression. The same instinct, will and determination to preserve their identity to this present day, was their bane: how can surrounding people accept a group that religiously refuses to mingle and adapt with them? Jews became the eternal ‘other’, allowing them to remain true to their identity, but also condemning them to stand out and, as the minority in most cases, the easy scapegoat.

As a quick aside: this is NOT an accusation towards the Jews, nor a justification for any oppression they suffered. It simply explains human behavior, warts and all, with cause and effect. Imagine a school, where a small group refuses to be associated with all the rest. As a minority, this invites being bullied and repressed. Where the repression might simply be cessation of invitations or overtures, affirming and consolidating the self-imposed isolation of that group, or anything worse.

Yet even that is too quick a characterization. The period of 500 to 1092 A.D. (the start of the first Crusade) is remarkably calm. Historians can only point to a single (1, one) event where local Jews were attacked, and either killed or forced to be baptized. Jewish historians confirm this, calling those 600 years the ‘Halcyon Days’ of Jews (halcyon: ‘denoting a period of time in the past that was idyllically happy and peaceful’), or describe it as ‘tranquil’, a period when Jews had ‘a favorable status’. The Church was stable, the faith was stable, and tolerated heresy and non-conformance.

That ended with the Crusades, and there is an uptick in attacks on Jews, notably centered in the Rhineland of Germany, in large part due to the very fractured nature of politics and power there. Equally notable is the role local bishops and clergy played in protecting the Jews, often placing their own safety and even life in danger by doing so. Still, a pattern of oppression and discrimination emerged. It is hard, at times, to distinguish the origin: local authorities, including church authorities, might ban mixed marriages or conversion from Christianity to Judaism. Yet what rules existed among the Jews prohibiting exactly those same things, but in reverse?

Either way, attacks became part of life, and where the attacks were not physical, distrust grew between both groups. In Spain, for example, the Reconquista that concluded in 1492 marked a difficult period for Jews: there were politics at play, and the fear of ‘fifth columns’ of Jews who only feigned to have converted to Christianity, but in reality remained Jews, marked them as ‘untrustworthy’, and likely allies of the Muslims that were just, at such great cost, evicted from Spain.

Curiously, but not surprisingly, with the rise of Napoleon, and the installment of stronger states in the wake after Waterloo, Europe saw a decline in attacks on Jews, in line with what we saw in the period between 500 and 1092 a.D. (with notable exceptions, as expressed with the Dreyfus scandal). Yet pogroms would increase in Eastern Europe, often very violently. It was similar climates of persecution that made Jews flee the Rhineland by 1500, and in the 1800s flee from Russia, many to the New World, others to the rest of Europe, and indeed even to the Holy Land. In later years, by the end of the 19th century, some started to return to their ancestral homeland, as the power and influence of the Ottoman Empire was waning, creating an opportunity that had not existed before. The Bilu, for example, had as goal the agricultural settlement of Israel. Harsh realities on the ground making farming not as easy as in Europe, and lack of funds, made this mostly Russian movement collapse.

Several waves of ‘Aliyah’ (literally from the Hebrew word meaning ‘ascent’ or ‘rise’, but now denoting ‘immigration to Israel’) followed, each wave classified based on reason, origin, etc. In the first phases this immigration was legal, with settlers purchasing the land from the local population, trying to establish farms.

The end of the 19th century is also the beginning of a movement that is known as Zionism. One can see Biblical precedence in the story of Moses, who told Pharaoh to "Let my people go!" Back to their promised land. The Babylonian exile is another, where 2 waves of returns, Aliyahs, saw Jews return to their ancestral lands. A first under the Persian king Cyrus the Great, in 538 b.C., who, upon conquering Babylon, decreed that the Jews were free again, and a later, second Aliyah, under Ezra and Nehemiah, in 456 b.C.

During the Byzantine-Sassanian War in 602-628 sees a revolt by the Jews, who were helping the incoming Sassanids against the Byzantines. They used that opportunity to try to gain autonomy again, but failed. Several people claiming to be the Messiah tried to incite uprisings, aimed at reclaiming Israel for the Jews, and the restoration of the Promised Land. This return had both political and religious overtones, as a return to political power, but under a ‘messiah’, a savior.

In a European intellectual climate that saw the birth of nationalism, communism, romanticism, rationalism, anarchism, etc., it is no surprise that Jews would also be influenced by those new ideas. The general decrease in attacks in Europe, physical or otherwise, on Jews is exemplified in the fact that so many Jews could rise to prominence in cultural, scientific and intellectual circles.

Take the idea of nationalism, for example. Jews liked that idea, but it made present a very painful reality: they had no nation of their own to feel nationalistic about... Which created a secular drive to support ‘Zionism’. The simple reality of wanting to avoid the constant pogroms and attacks was another drive to want their own state, and the right to protect themselves, from a very secular point of view. A lot of people did not care as much about the Messiah or God’s promises, but wanted a place they could call their own, and legally and properly defend themselves, so no one would attack them anymore.

Unknown to most, Napoleon Bonaparte had written an open letter to the Jewish Nation, on April 20, 1799, starting: “Buonaparte, commander-in-chief of the armies of the French Republic in Africa and Asia, to the rightful heirs of Palestine.”

Napoleon continued:

“Arise then, with gladness, ye exiled! A war unexampled In the annals of history, waged in self-defense by a nation whose hereditary lands were regarded by its enemies as plunder to be divided, arbitrarily and at their convenience, by a stroke of the pen of Cabinets, avenges its own shame and the shame of the remotest nations, long forgotten under the yoke of slavery, and also, the almost two-thousand-year-old ignominy put upon you; and, while time and circumstances would seem to be least favourable to a restatement of your claims or even to their expression, and indeed to be compelling their complete abandonment, it offers to you at this very time, and contrary to all expectations, Israel's patrimony!”

This did not come to pass, as his adventures overseas came to an end when he was forced to retreat from Acre on May 22, 1799, never to come back to fully conquer Israel. Yet the idea was now firmly planted in European minds: the idea to be a new Messiah, ushering in the revival of Israel.

Tied with a British Protestant revival , early 1800s, a new interest in Israel rose in England and the United States, in the decades immediately following Napoleon. Anita Shapira, a respected Zionist historian, writes: “… until the nineteenth century the Bible was considered secondary to Jewish oral law… It was the Protestants who discovered the Bible …Even the idea of the Jews returning to their ancient homeland as the first step to world redemption seems to have originated among a specific group of evangelical English Protestants that flourished in England in the 1840s; they passed this notion onto Jewish circles.”

A ‘Memorandum to Protestant Monarchs of Europe for the restoration of the Jews to Palestine’ was printed in the newspapers, urging, with very strong religious language, the founding of a Jewish state.

Important to notice, are the following statements by Jewish authors on Zionism:

Geoffrey Alderman wrote in the Jewish Chronicle: “The Balfour Declaration was born out of religious sentiment. Arthur Balfour was a Christian mystic who believed that the Almighty had chosen him to be an instrument of the Divine Will… perhaps as a precursor to the Second Coming of the Messiah”. (Geoffrey Alderman, Jewish Chronicle November 8th 2012)

Tom Segev wrote: ‘The [Balfour] Declaration was the product of neither military nor diplomatic interests but of prejudice, faith and sleight of hand. The men who sired it were Christian and Zionist and, in many cases, anti-Semitic.’ (Tom Segev, One Palestine Complete, p33)

Rabbi Danny Rich wrote: ‘I am not arguing for Zionism as a Christian idea, but it is a very interesting point to make. Many of the non Jews who supported Zionism did so out of their Christian understanding of what was happening.’

In the US, John Smith, founder of the Latter Day Saints (the Mormons) sent someone to dedicate Israel ‘for the return of the Jews’, and Protestant theologian William Eugene Blackstone submitted a petition to the US president in 1891, calling for the return of the Jews to Palestine, giving them that land.

It was Theodore Herzl, a young Hungarian journalist who lived in Austria, to bring all those ideas together into a powerful idea called ‘Zionism’. During the First Zionist Congress, planned by Herzl and Nathan Birnbaum, the ‘Basel Program’ was accepted:

Zionism seeks to establish a home for the Jewish people in Palestine secured under public law. The Congress contemplates the following means to the attainment of this end:

* The promotion by appropriate means of the settlement in Palestine of Jewish farmers, artisans, and manufacturers.

* The organization and uniting of the whole of Jewry by means of appropriate institutions, both local and international, in accordance with the laws of each country.

* The strengthening and fostering of Jewish national sentiment and national consciousness.

* Preparatory steps toward obtaining the consent of governments, where necessary, in order to reach the goals of Zionism.

Where this was a political answer, seeking the approval of foreign rulers to enable a Jewish homeland, cultural counter-ideas came up as well, such as ‘Cultural Zionism’, the idea that Jews must revive their own culture, identity and language, i.e. through a resurrection of their ancient language, Hebrew. Keep in mind, up to that point, Jews spoke Aramaic, Yiddish (or various dialects thereof), or the local language. Hebrew was preserved as a literary and religious language.

A battle took place between political streams, most notably socialism, and the orthodox religious groups. Even the more liberal group of ‘Reform Judaism’ rejected Zionism, and stated: "We consider ourselves no longer a nation but a religious community, and therefore expect neither a return to Palestine, nor a sacrificial worship under the administration of the sons of Aaron, nor the restoration of any of the laws concerning the Jewish state." To make matters more complicated, in Eastern Europe there was the General Jewish Labour Bund, calling for Jewish autonomy WITHIN Eastern Europe, with Yiddish as their national language. They opposed Zionism and orthodox Judaism alike. This Bund was part of the rising socialist activism.

Under Marxist dialectic, the whole language of the oppressed and the oppressor, lent itself perfectly to be applied to the Jewish experience. Proponents of this socialist Zionism (which included people such as Israel’s first prime minister, David Ben-Gurion) claimed that a new class system had to be constructed, to create a ‘normal’ class structure. Socialist Zionist Aaron David Gordon wrote "the land of Israel is bought with labour: not with blood and not with fire." This was in line with the efforts of so many others already, including the work done to drain the ubiquitous malarial swamps (which both helped eliminate malaria, a main killer in the area at that time, and create excellent and fertile farmlands), making it very easy to co-opt those efforts in the socialist agenda.

The result: a very fractured Jewry, unable to come to a unified plan, let alone action.

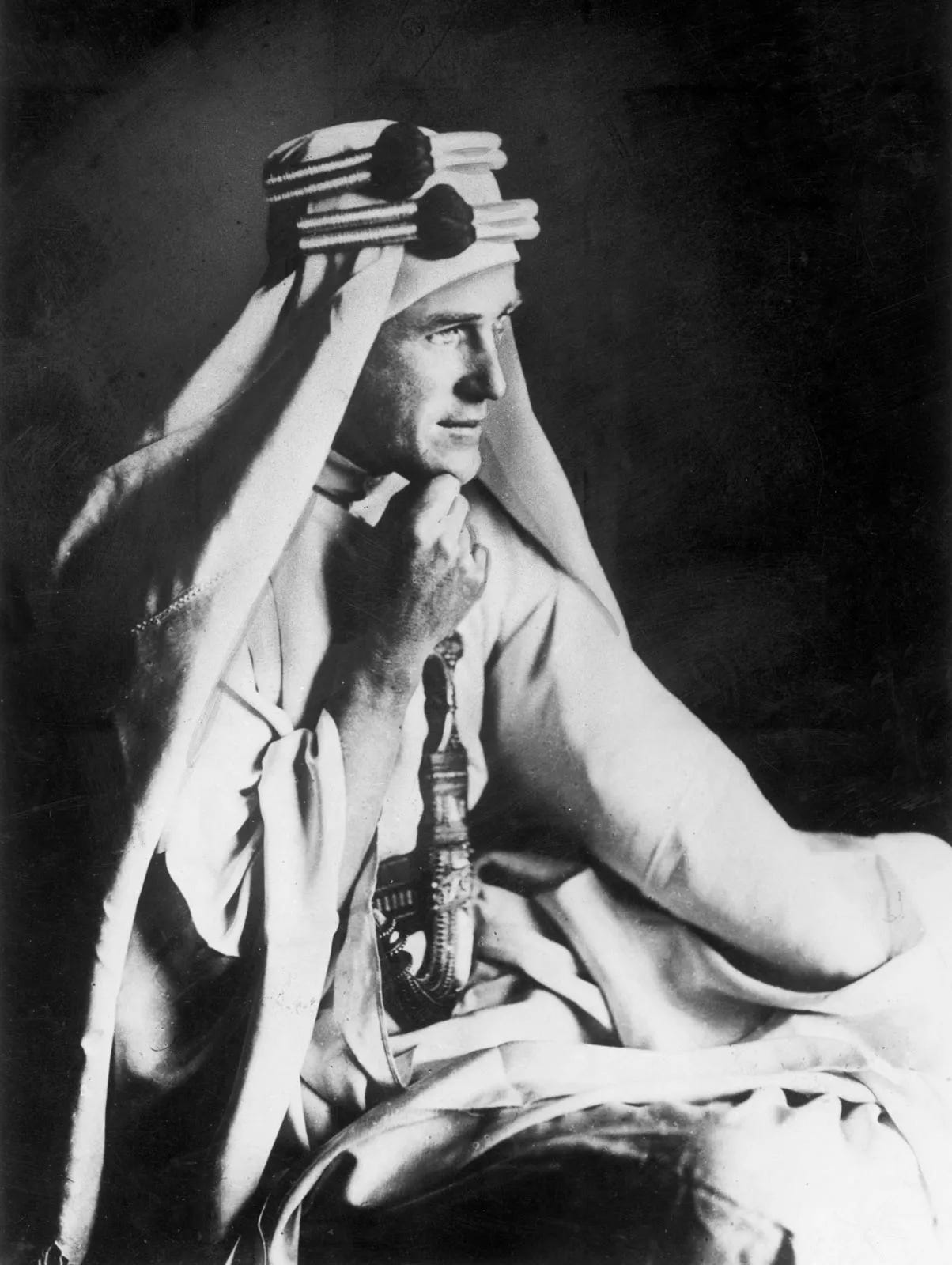

Things really started to change by the end of World War I, when the Allied forces defeated Germany, Austria and the Ottoman Empire. It was the British who attacked the Ottomans from the South, first Egypt, then the Sinai, Palestine, while including the Arabs from what is now Saudi Arabia. (Remember Lawrence of Arabia? He was a British intelligence officer tasked to incite the Arabs to rise up against the Turkish Ottomans!)

At the beginning of the war, Cabinet member Herbert Samuel presented a memorandum named The Future of Palestine to the British Cabinet, explaining in detail the benefits of a British protectorate over Palestine to support Jewish immigration. Two years later, the Balfour Declaration was made, where the British Foreign Secretary, Arthur Balfour, gave a public expression of the fact that the government was in favor of "the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people", and specifically noting that its establishment must not "prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country".

Interesting is that most Jews supported Germany and the Ottoman Empire in this war, in part because the Russians were allied against them, and were at that time the largest culprits of antisemitic laws, expulsion, and killings, in part because they depended on the benevolence of the Kaiser and the Sultan to be allowed to come and settle in Palestine. Yet the British overlooked all that, as the main drive of men like Samuel and Balfour was religious, not political.

When in 1917 the October Revolution took place in Russia, many leaders of the new Bolshevik government were Jews or supportive of the Jewish desires in regards to Zionism. Between 1922 and 1928, with help from donations from US Jewish charities, the Soviets enacted a plan to train Ukrainian Jews in agricultural communes, to prepare them for Kibbutz life. Even with disagreement on the stance regarding communism, these elements explain the balancing relation between current day Israel and Russia.

To help win the war, the British enlisted the help of the Arabs against the Ottomans, promising, among other things, land and control in Palestine. They also made promises to the Jews, such as expressed by the Balfour declaration. When the war was over, the newly created League of Nations endorsed the full Balfour declaration, and formed the British Mandate for Palestine.

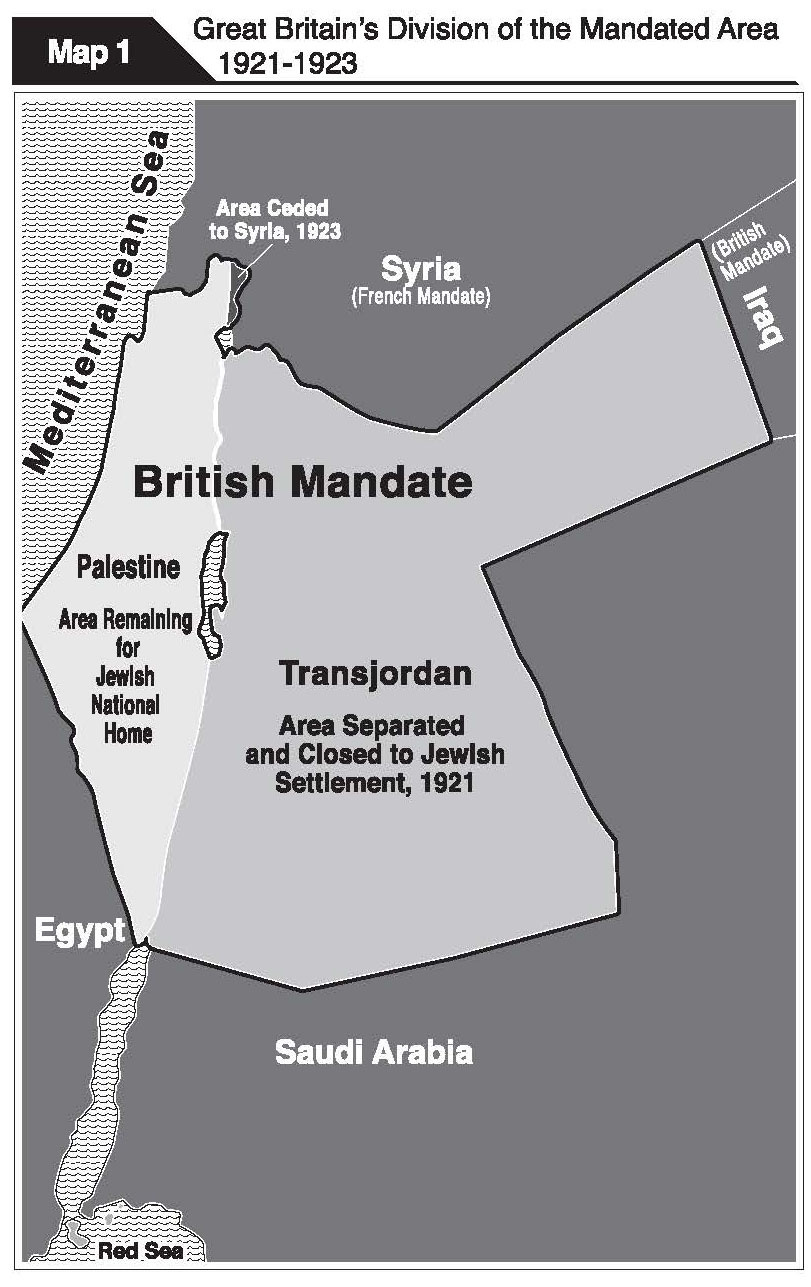

This is the territory of the British Mandate for Palestine. Notice how ‘Palestina’ is a whole lot larger than the current day territory of Israel.

Let’s take a step back. In 1919 Hashemite Emir Faisal, signed the Faisal–Weizmann Agreement. He wrote:

We Arabs, especially the educated among us, look with the deepest sympathy on the Zionist movement. Our delegation here in Paris is fully acquainted with the proposals submitted yesterday by the Zionist organization to the Peace Conference, and we regard them as moderate and proper.

And Weizmann, President of the Zionist Organisation, had assured:

The Jews did not propose to set up a government of their own but wished to work under British protection, to colonize and develop Palestine without encroaching on any legitimate interests.

There was, from the beginning, a cordial relation between the Hashemites and the Zionists, which for good part remains to this day.

Among other things, this led to the following situation, where immigration of Jews was only allowed in the western part of the Mandate area:

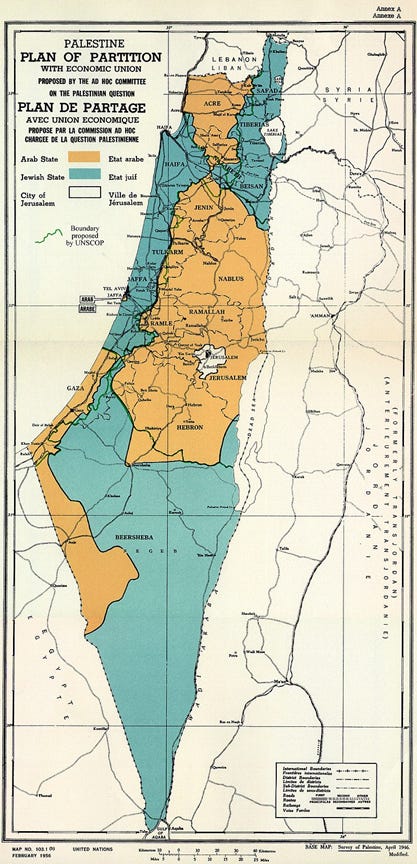

Instead of the full mandate area for the new Jewish state, only a small part would be dedicated to that goal.

Interesting to note is the names.

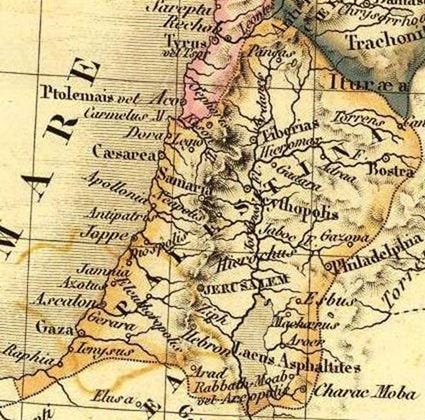

This 1839 map shows Palestina, crossing the Jordan river:

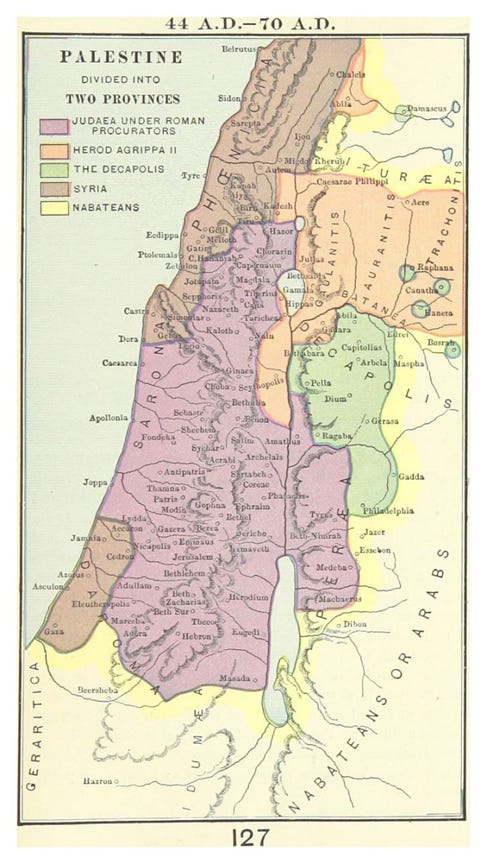

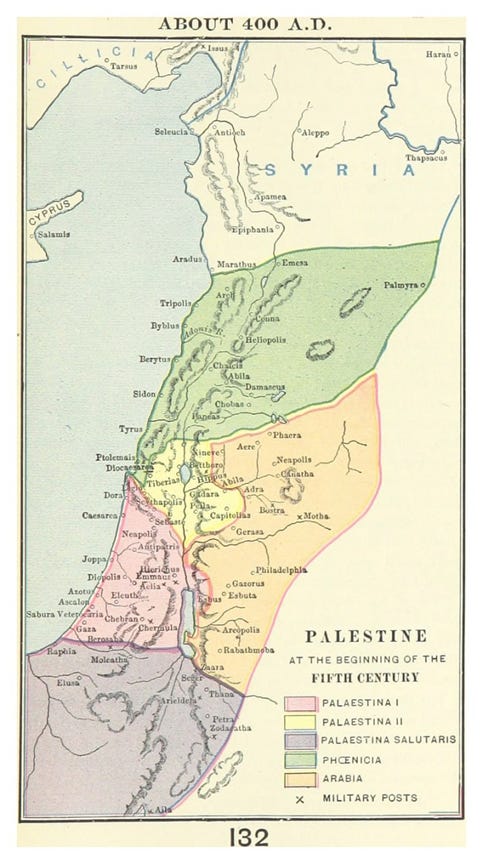

Even under Roman rule, the territory was larger than current day Israel:

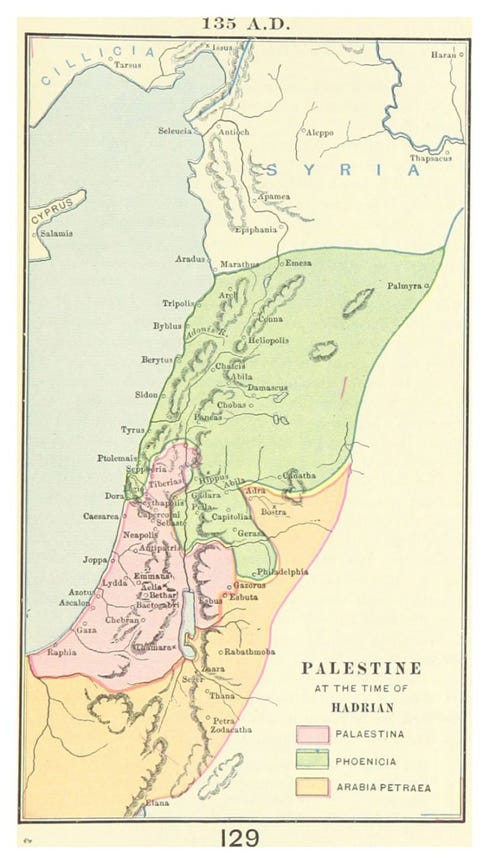

This is what emperor Hadrian created (notice ‘Aelia’ where Jerusalem is):

And a good 2 centuries later, you get a map like this, where the territory of Palestina was cut into 3 parts, stretching well into the Sinai desert....

I find this rather interesting. Based on these facts alone, THERE ALREADY IS A PALESTINIAN STATE, namely Jordan. What did the second half of the British Mandate for Palestine become? The Emirate of Transjordan (NOT ‘Jordan’!) was established in 1921 by the Hashemite Emir Abdullah I, as a British protectorate. Transjordan. Which is short for Palestina Trans-Jordania, as opposed to Palestina Cis-Jordania. Palestine on THIS side of the Jordan, vs Palestine on THAT side of the Jordan. If you look at the maps, at the names, yes, there is a core of Palestina on the western side of the Jordan, but one cannot deny that there is a Palestine on the OTHER side, as well. If only politics were ever so simple, we would not have seen all that bloodshed and hatred over the past decades, over a Palestinian homeland. Which they technically already have, in the Kingdom of Jordan. But that as an aside.

The growing Jewish immigration, their purchases of land, the transformation of said lands, and the political situation (with the end of the Ottoman Empire, the Arab aspirations, the Jewish dreams, the promises made to both Arabs and Jews), which should come as no surprise, created increasing instability and resentment among the local Arabs and Bedouins.

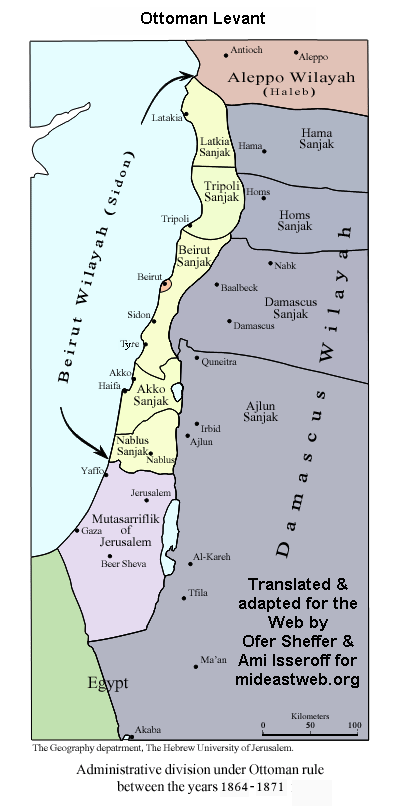

To complete this history by maps, here is the administrative division under Ottoman rule, between 1864-1871. No trace of ‘Palestine’, either.

The first clashes of violence took place (well, there were many more clashes before, but the growing influx of Jews, who legally and properly started buying land and houses, often at very high price, precipitated a new wave of violence against them), starting with the 1920 Battle of Tel Hai (where Jewish settlers defended their settlement against a raid by Arab militia, in context of the Franco-Syrian war), the Nebi Musa riots, the 1929 Buraq uprising about access to the Western Wall, the 1933 riots, a full on armed Arab revolt in 1936-1939, the 1938 Tiberias massacre where 19 Jews, including 11 children, were killed, and many others. This was well before there was any talk of ‘colonizing’ or ‘occupation’…

These and other such events (as well as the realization that the only way to defend against pogroms is to have your own armed guards) led to the founding of armed groups like Haganah, Irgun, Stern and Beitar. Some would become notorious for what can only be described as terrorist attacks, in line with the modus operandi of the anarchist groups from the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Each had their own goals and methods, and would not always work together.

On top of that, centuries of oppression in Islamic countries, aimed at Jews, even before the word ‘Zionism’ was coined, and before there was any attempt to settle in Israel again, undercut any idea that violence in Israel against Jews is only due to their ‘colonialism’ (more about that later).

In a key address to the Political Committee of the U.N. General Assembly on the morning of November 24, 1947, just five days before that body voted on the partition plan for Palestine, Egyptian delegate Heykal Pasha declared, in what is a full-on threat: “The United Nations ... should not lose sight of the fact that the proposed solution might endanger a million Jews living in the Moslem countries. ... If the United Nations decided to partition Palestine they might be responsible for very grave disorders and for the massacre of a large number of Jews.”

And in the early months of 1948, Matiel Mughannam, an Arab Christian born in Lebanon and the leader of the Arab Women’s Organization, stated:

[A Jewish state] has no chance to survive now that the ‘Holy War’ has been declared. All the Jews will eventually be massacred.

Abdul Rahman Hassan Azzam, the Secretary-General of the Arab League, declared in 1947 that, in the event there would be war because the establishment of a Jewish state, it would lead to "a war of extermination and momentous massacre which will be spoken of like the Mongolian massacre and the Crusades."

Up to the last moment, threats about violence and massacre against Jews all over the Arab world, not even those in Israel, were made.

Jewish groups started to return violence in a more and more organized way. For example, in 1946 Irgun bombed the King David Hotel in Jerusalem, where the British had their administrative headquarters. Earlier, in 1944, Lehi (also known as Stern, after its founder) assassinated Baron Moyne, British minister of state in the Middle East. Attacks like that on Deir Yassin, as seen through international eyes, similarly did a lot to destroy goodwill towards Israel.

But that escalation happened in direct response to World War 2. Where the Jewish world was hopelessly divided before that war, the unspeakable horrors that the Nazi regime inflicted upon Jews in the concentration and destruction camps were a complete shock. Now every Jew agreed: never again. Never again will they be led to slaughter like lambs. They needed their own country, and the ability to defend themselves. All disagreements were cast aside, in favor of their one, shared goal: the creation of a Jewish state. During WWII, groups like Stern and Irgun started to ramp up their own violence, unwilling to sit by idly any longer, and alarmed by the bloodthirsty war rhetoric of the surrounding Arab nations.

Another result of the killing of so many European Jews by Nazi Germany was that the focus of power within the broader Zionist and general Jewish world shifted to the American Jews. At the same time, the UK was severely weakened, unable to exert much pressure in their Mandate Territory. Many of the surviving Jews from Europe were now very desperate to leave Europe, and made for the Promised Land. Nothing could stop them. They needed, required, demanded a safe haven, a place they could call their own.

On 29 November 1947, the General Assembly of the newly created United Nations, successor to the failed League of Nations, adopted a resolution (181 II) that recommended the adoption of the partition plan for Palestine.

Jews in the Mandate territories celebrated this as a victory, but the Arabs rejected it completely, even though it represented a further division of the original plan of the British Mandate in Palestine. A civil war broke out between Arab Palestinians and Jews, with the Arabs helped by units from the Arab Legion (the regular army of Jordan). Since the British were still responsible for this territory, weapon shipments to the Jews were prohibited, but smuggled in anyway, among others by the Haganah and foreign volunteers. In many cases, the British simply held to a hands-off approach, and let both sides be. Focused more on their retreat, and unwilling to risk more lives of their soldiers, British soldiers idly stood by.

Despite all odds, the Haganah managed to hold their ground, and in the last weeks even gain substantial ground. This civil war lasted until May 15, 1948, the day following the end of the British Mandate. On that day, May 14, David Ben-Gurion proclaimed the Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel.

“In the Second World War, the Jewish community of this country contributed its full share to the struggle of the freedom- and peace-loving nations against the forces of Nazi wickedness and, by the blood of its soldiers and its war effort, gained the right to be reckoned among the peoples who founded the United Nations.

On the 29th November, 1947, the United Nations General Assembly passed a resolution calling for the establishment of a Jewish State in Eretz-Israel; the General Assembly required the inhabitants of Eretz-Israel to take such steps as were necessary on their part for the implementation of that resolution. This recognition by the United Nations of the right of the Jewish people to establish their State is irrevocable.

This right is the natural right of the Jewish people to be masters of their own fate, like all other nations, in their own sovereign State.

ACCORDINGLY WE, MEMBERS OF THE PEOPLE'S COUNCIL, REPRESENTATIVES OF THE JEWISH COMMUNITY OF ERETZ-ISRAEL AND OF THE ZIONIST MOVEMENT, ARE HERE ASSEMBLED ON THE DAY OF THE TERMINATION OF THE BRITISH MANDATE OVER ERETZ-ISRAEL AND, BY VIRTUE OF OUR NATURAL AND HISTORIC RIGHT AND ON THE STRENGTH OF THE RESOLUTION OF THE UNITED NATIONS GENERAL ASSEMBLY, HEREBY DECLARE THE ESTABLISHMENT OF A JEWISH STATE IN ERETZ-ISRAEL, TO BE KNOWN AS THE STATE OF ISRAEL.”

The very next day, with the British Mandate officially over, and the Jewish State of Israel declared, the surrounding Arab states, Egypt, Transjordan, Iraq and Syria, attacked with their armies, soon reinforced by troops from Lebanon, Saudi Arabia and Yemen and a host of Arab volunteers.

Miraculously, Israel came out standing, having gained territory, and the right to live another day.

Excellent history!