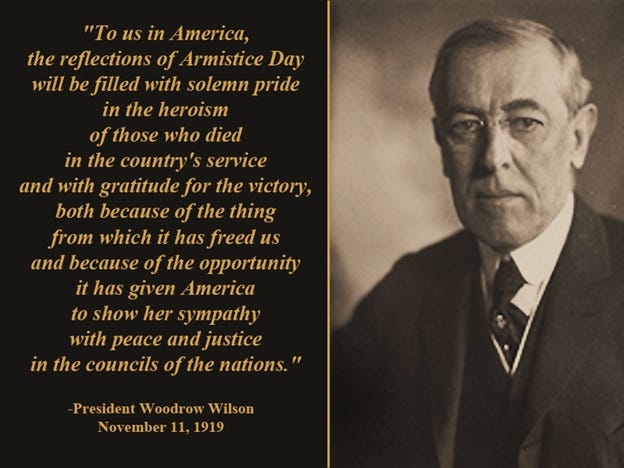

Today, on November 11th, the United States celebrates Veteran's Day. I know it as Armistice Day, as it is celebrated as such in Belgium and across Europe. President Woodrow Wilson instituted this day on Nov. 11, 1919, with these words:

"To us in America, the reflections of Armistice Day will be filled with solemn pride in the heroism of those who died in the country's service and with gratitude for the victory, both because of the thing from which it has freed us and because of the opportunity it has given America to show her sympathy with peace and justice in the councils of the nations."

He’s right, and I celebrate with him and my American friends and veterans that I know personally this sacrifice from those who gave all, as well as the sacrifice of those who did come back after their service.

So I honor my son, who just started ROTC for the US Army. Not a veteran yet, but he started to walk that path of service and sacrifice.

I honor my brother, who was in the Belgian Special Forces.

I honor my uncle, who was in the Belgian Navy.

I honor both my grandfathers. I honor my great-grandfather (see picture below).

I honor a forefather who was a dragoon in the Napoleonic Era.

But with this remembrance of the military service of my own family members, I would like to add this Belgian/Flemish perspective.

11-11-11 is the code we all know and are taught since kindergarten. The 11th hour, of the 11th day, of the 11th month. A little over 100 years ago... The moment the guns finally fell silent, after 4 years of a war that was so horrible people just wanted to forget about it. A war that left a horrific scar over hundreds upon hundreds of miles. Even today, on the mere 20-30 miles of front lines that stretched across Belgium, every single year (to this very day!) between 150 and 300 tons (sometimes a lot more) of unexploded ammunition are found and disposed of!

But this harvest at times gets also much more personal:

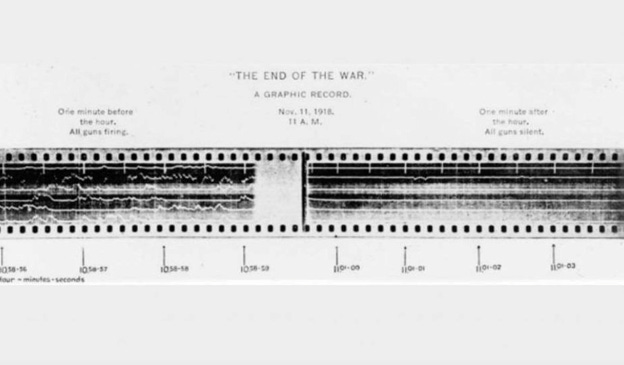

The next image is the output from an early artillery warning and location system, that used sound triangulation to locate the position of enemy artillery batteries. The second is an image from a French version of such ranging system, notice the ‘film spool’ on the right. The above example is from the very last minutes of the war, when batteries all over the front erupted in a last, insane, pointless and murderous volley -nothing different from the 4 previous years, really- shooting away whatever ammo they had still laying around. The silence that followed must have been otherworldly to the soldiers, dazed, crawling out of their bunkers, fox holes, hiding places, struggling with the disbelief that this nightmare could really be over…

It is hard for us to appreciate that silence that fell over the front on that day, and how thunderously loud that silence must have sounded to the soldiers, some waiting in their trenches, guns in hand, or to those who were ordered into a last, futile attack, as each side fired everything they had at each other in those last hours before 11am.

A silence of relief, of disbelief, of shock, of a sadness heavier than anything. The jubilant celebrations were for the civilians at home, as the wives, the mothers, the fathers, the children of the soldiers sang and danced. Those who survived the fighting, the stench of death, of mud and blood after 4 years of horror still on their clothes, hands and soul, just kept silent. Let’s join that silence for a moment today. In gratitude for those who shouldered the burden of defense and protection.

A look at the war graves tells a story about war, silently, yet poignant. Visit a French war grave, and one sees a post-Romantic heroic celebration of the victorious dead. Very dated, it stands in chilling contrast with the reality of the butchery that took place for years and years. The British commonwealth grave sites are sublime, in that they managed to understand the real cost, and understated the visual presentation. Simple white slabs, with a name, a regiment symbol, a date, and sometimes a heartbreaking verse left by the family ("We have lost, heaven has gained, one of the best, the world contained"). Laid out in strict lines, it is as if the gravestones still stand in attention, as silent onlookers to our own deeds, reminding us of the price they had paid. The gravestone of another British soldier, somewhere in Flanders Fields, has this inscription: “Our sacrifice is in what we have lost. His, in what he has given.”

My oldest son had the opportunity to visit these battlefields when visiting his grandparents a year or two ago. With a friend of my father, who is a special forces veteran, they visited several Normandy WWII sites, but also the Belgian front-lines of WWI and the Somme battlefield. At the Somme battlefield, they were walking a small field, to look for artifacts. Something happened to him on that field: a sudden realization of the reality and horror of war, so powerful that when he came back to tell me, I looked in the eyes of a man, heavy with a sorrow that was not just his own. He tells that story as follows:

“The most remarkable I did during my stay in Belgium, was visiting battlefields, from World War 1 and World War 2. They all have something imposing, solemn. It gives you the feeling you get when you step into an old cathedral, where you feel the urge and need to pay your respect just because of the sacredness of the space you walked into. On the Somme Battlefield this feeling wasn’t sacredness, but a persistent restlessness, unease, an almost nauseating feeling that fills you when you are there.”

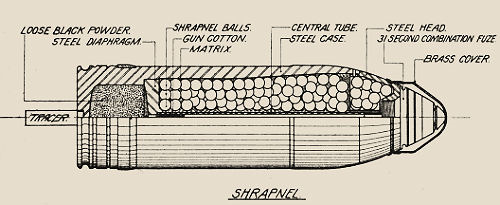

At every step he found at least 1 small lead ball, from shrapnel grenades that would have exploded overhead. Here and there he found bullets, in their casing, unfired, and once in a while also a button. “A soldier died there,” his guide explained. His guide also found a small bone fragment. “Most likely human...” That fragment was carefully placed back in a small hole in the ground, and covered again. And everywhere, and I mean everywhere, shards of metal. Large, small, but always cruelly sharp and frayed. My son continued his story: “When I walked there and saw the iron fragments everywhere on the ground, bullets, shrapnel balls, even a grenade, on that small farmer’s field, so insignificant and unimportant compared to the whole battlefield itself, and thought about how I saw only those fragments that were left after all that time, just the ones visible on the surface, without digging, more than a hundred years after the end of that battle itself, I suddenly realized the absolutely mind-blowing violence that must have had taken place to offer such a result that remained so present so many years later. I stood still, and could only stare around me... It took me a while before I started moving again. This is what war is...”

He also visited several war cemeteries: American, British, German, Belgian, French,... “The French and Belgian cemeteries were the least organized and maintained. While I found the German grave sites much more organized, I thought them less appealing or not as beautiful as they could have been,” my son continued. “The American cemeteries, however, were exceptionally arranged, very well maintained, and sublimely beautiful, with flowers and well pruned bushes and trees. [He admitted, when I asked him about Tyne Cot Cemetery, that the British Commonwealth War Graves are a match to that]. At the American grave sites walking trails were laid out, and monuments erected, much less so on the French and Belgian military graveyards. During my visit that was what I was most proud of about America: the sense that Americans have to honor and thank those who sacrificed their all, who gave their lives for their country. It felt to me as if European countries did not grasp that as deeply, or not quite.”

But there is another step up to fully grasping what had happened in those terrible 4 years, only hinted at in his recollection of his visits: the German cemeteries. Devoid of any victory, glory, or heroism, they hold up an image of peace, heavy as lead, dripping with blood. The Germans understood even more painfully than the British or Americans: in the end, nobody won, everyone lost. In small spaces (the German cemeteries are never large), thousands upon thousands of soldiers lay buried, often most are unknown, piled together in mass graves. Nature seems to quiet down, even the sun seems less bright when you enter these sites.

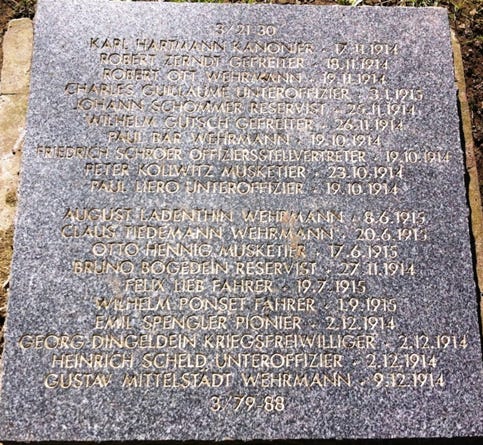

Small flat square stones are lining up on the grass, and hold 10-20 people at a time, showing name, rank/specialty and day of death. Sometimes they hint at a story, when you suddenly see about 6 names, all ending with “Kanonier, 14-06-1917” and a single one that said “Unteroffizier, 14-06-1917”. An artillery battery got hit in counter fire, and the whole crew perished…

Amidst those flat grave markers stand spread out throughout the field small groupings of three roughly hewn crosses. And that is it. Somber. Chilling to the bone. Here one meets the true face of war.

In Vladslo a German war cemetery contains the remains of over 25,000 German soldiers. One of them is Peter Kollwitz, 17-year-old son of the famed German sculptor Käthe Kollwitz, who died at the beginning of the war, October 23rd, 1914, in nearby Esen. As monument to her son Käthe made a group of sculptures that is absolutely haunting: the mourning parents (Trauerndes Elternpaar). It shows a father and a mother, united in mourning, yet so different and separated in the way they try to cope with their loss. You see the father trying to control his pain, arms crossed over his chest, back straight, looking straight ahead, fighting back the tears that are welling up. In contrast, the mother, bent over, broken, crying, exuding warm motherly love, not just a mother to Peter, but to all the men who perished at the front, and are buried right alongside her own Peter.

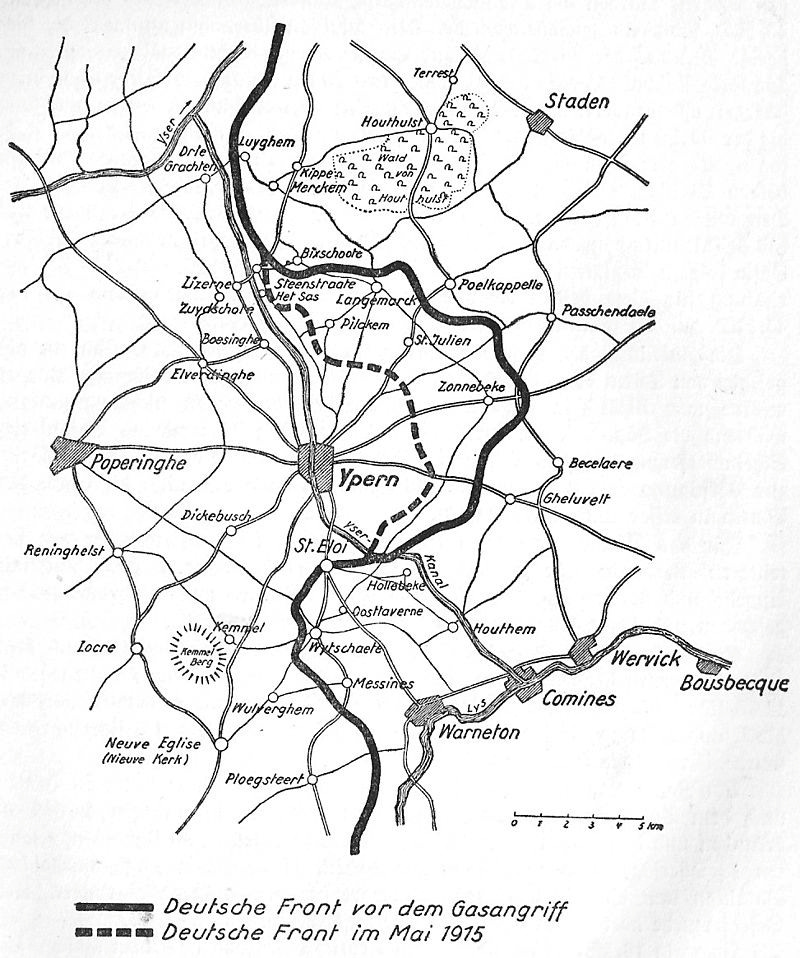

Canadian readers will know this next poem. It haunts me, on this day. One of the earliest poems I learned by heart. Composed by Canadian Lieutenant-Colonel John MacRae, a physician, and a poet. He wrote it early May 1915, after he had presided over the funeral of a dear friend of his. Lieutenant Alexis Helmer had died in the second battle for Ypres, that had started on April 22nd, and would rage for a few more weeks, until May 25. That battle had the macabre distinction of being the first battle that saw widespread use of poison gas. The Germans managed to push back the British, who heroically fought and managed to minimize the German advance.

I can’t imagine the state of mind Lt.-Col. MacRae must have been in. Having lost his friend, having seen all the mangled corpses pass by, having had to work on hopelessly maimed and wounded soldiers, trying not just to save them, but to save as much of them as possible. Having seen for the first time the horrendous wounds and suffering caused by mustard gas… Looking at his poem, he was angry, livid even, while dejected and struggling to grasp what had really happened. Yet defiant, too, and with half an accusation, half a missive, he asks us to take up the quarrel with the foe: not the Germans, I believe. He had certainly treated German prisoners as well, and noticed they bled just the same red blood as his fellow Canadian and British soldiers. He likely aimed it at another foe, one that drove to this tumult, out of the trenches, in the clouds…

With a glimpse of despair, then, trying to find meaning in his suffering and sacrifice, the sacrifice of his friend, and the suffering of his fellow soldiers, we are asked to take over the torch, thrown to us from failing hands.

Not to burn down, in an endless cycle that renders any sacrifice meaningless, but to bring light, and peace, as the ultimate goal and dream of those who remained behind...

Lt.-Col. MacRae would write about that experience in a letter to his mother:

“For seventeen days and seventeen nights none of us have had our clothes off, nor our boots even, except occasionally. In all that time while I was awake, gunfire and rifle fire never ceased for sixty seconds ... And behind it all was the constant background of the sights of the dead, the wounded, the maimed, and a terrible anxiety lest the line should give way.”

The war would exact a heavy toll on him. Having contracted pneumonia, he also got cerebral meningitis, and died late January 1918. He did not see the end of this nightmare…

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie,

In Flanders fields.

Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.

Having grown up 'In Flanders Fields', I find it hard to say ‘happy Armistice Day’. The memory, for me, is that of a horrible nightmare, of a multitude of at times deadly scars still visible in the landscape, still killing people with left-over ammunition, still weighing heavy on the mind and soul of Europe. While happy that hellish war is over, the memory of it is not a happy celebration. When will we ever learn?

One of the angriest lines I know were written by another British war poet, Wilfred Owen. He describes the complete horror of the effects of poison gas on a friend of his, in bloody and visceral detail, ending with a quote from the Roman poet Horace, with such vitriolic fury exposing the madness of those sending them to war, spitting out those Latin words like bullets from a machine gun, with such powerful disdain, frustration and rage: “How sweet and fitting is it, to die for one’s country.”

If in some smothering dreams, you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,—

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.

Living in the United States now, I do celebrate Veterans' Day on top of Armistice Day. Both remembrances, after all, point at the same reality, and give us the same lesson. Do remember those who sacrificed, then and now, and reflect on this: be a peacemaker, not just in the grand scheme of things, but especially in the small day to day life you lead. Honor the dead (and those that came back), by living out the peace they paid for. We owe them that much.

_________________________________________________

If you liked this read, please share with friends and family!

Addendum:

I have to share this French song, as well. The video shows actual footage of the war, and in the middle part it shows shell-shocked soldiers. It is harrowing: industrialized war became so adept at killing, that it did not just kill and maim bodies, but also the minds of the soldiers. It is a must-watch, to get an idea of that ‘Forgotten War’, so horrible that people did not want to think about it, or even talk about it. The gay twenties was the ultimate expression of that escapist attitude.

The refrain captures the plight of a soldier well:

Chante, oh chante, ma belle!

Prie pour moi dans les batailles,

Prie pour moi et pour mes frères,

J’ai bien peur de te revoir jamais!

Sing, oh sing, my beauty!

Pray for me in the battles,

pray for me and for my brothers,

I’m really afraid to never see you again!

Harrowing, this war... More than any other, I’d dare say, even if the horror of each is the same.

When I was a child, the man who lived next door, 'Mac', was a WWII vet. Later, we moved and again we lived next to a WWII Vet, Mr. Martz who fought at the 'Battle of the Bulge'.

I was born 15 years after the end of WWII, but it is only now in my later years that I can appreciate how fresh those memories must have been for those Men. 15 years ago to me now seems like only yesterday.

Sadly, today most of what we know of Total Warfare only comes from a skewed Hollywood' treatment of it.

We are fortunate to have not experienced it. As a US Navy retiree 20 Yrs on, I've always been uneasy with any acknowledgement on Veteran's Day - I've never desired or felt worthy enough for a parade.

You're right, today should be for reflection and reverence. A day of prayer that the world never experiences these terrible days ever again.

Thank you!

For me, WWI will always be the one, horrible face of War, more so than all the following wars with their death, destruction and suffering.

Remembrance Day infallibly has me in tears. The poem 'In Flanders Fields' is too poignant not to cry, as are the photos of the war cemeteries.

The one image which for me encapsulates the total futility of war and those deaths is the closing sequence in the 19330's b/w version of 'All Quiet on the Western Front', where the protagonist sees a butterfly on the trench wall and is shot to death while reaching his hand out in wonder.

Over 100 years later, and we - or rather: our politicians still have learned nothing, their facile 'commemoration' notwithstanding.