Part 1, Is Russia’s cause justified? The historical run-up

Part 2, A just cause in the face of violence and a Neo-Nazi resurgence

Part 3, A just cause in the face of violence, deceit, and a policy of regime change

Part 4, Some history and background on bioresearch

Part 5, Ukrainian biolabs and US attitude towards bioresearch

Part 6, Use of chemical weapons in Ukraine confirmed

Part 7, Russia is NOT the aggressor…

Part 8, …but the US, NATO and EU are!

Part 9, America’s nuclear gambles.

Part 10, Are we the baddies?

________________________

Longread

Russia: Their cause to go to war is complex, but both long-coming and immediate. In this series of articles, I will explore in this first installment the background of Russia's war (fall USSR until 2014). In part 2 I explore the immediate repercussions of 2014, the ‘first invasion’ of Russia when they annexed Crimea, the violence that resulted from that coup and the Neo-Nazi resurgence, and in part 3, the response of the Ukrainian government, several stories of deception by the West of Russia, all the way up to their second invasion of the Special Military Operation that began on February 24, 2022. These first 3 articles aim to show how Russia's cause to go to war is just, or, even more pointedly stated, how this war is now the US’ war.

Part 4 will offer an exploration of how Russia's war can be seen as legitimate under Just War Theory (Which includes 'cause needs to be just' as a requirement, as laid out already in the previous parts). And finally, in part 5, we will take a look at how the US is the aggressor, citing their provocations, deceit, the difference in nuclear doctrine between Russia and US, etc.

Stay tuned!

______________________________________________

To talk about what is going on, a not-so-quick history lesson is required.

On November 9, 1989, when the Berlin Wall fell, a chain reaction was set off. First, the genie of unification, and the idea of overthrowing the Soviet overlords (as well as the realization that they COULD be overthrown!) was now present in Europe, and would never leave. Second, UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and French President François Mitterand were opposed to the German reunification, afraid of the new power balances, and of a resurgence of German power and influence (these ‘old powers’ do not ever forget nor forgive), and urged Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev to do what he could to stop this process of reunification that was set into motion by the fall of the Wall (followed by the fall of the internal border between West and East Germany within the same month).

While an end to the Soviet Union was still unthinkable, many high level meetings took place to guide this transition of the former East German republic into a unified Germany, which was member of the EU and of NATO. Gorbachev, already on loose footing after the Baltic states started the path to break with the Soviets in 1988, had a very difficult task: to deal with this new reality, without starting war, and without pushing away the hardliners back home in Moscow.

One such meeting was between US Secretary of State James Baker and President Gorbachev, on Feb 9, 1990.

An LATimes article from 2016 recalls that as follows:

“In early February 1990, U.S. leaders made the Soviets an offer. According to transcripts of meetings in Moscow on Feb. 9, then-Secretary of State James Baker suggested that in exchange for cooperation on Germany, U.S. could make “iron-clad guarantees” that NATO would not expand “one inch eastward.” Less than a week later, Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev agreed to begin reunification talks. No formal deal was struck, but from all the evidence, the quid pro quo was clear: Gorbachev acceded to Germany’s western alignment and the U.S. would limit NATO’s expansion.”

Because no formal deal was struck, people have maintained that the claim by the Russians, and lately strongly by Putin, that the West and NATO have broken their promise that NATO would NOT expand eastwards. Of course, this was repeated a lot more and a lot stronger after the start of the Special Military Operation end of February 2022.

In a four part apologetic against Russia, titled ‘Warrant for an Invasion: The Myth of the “American Coups” in Ukraine. 4. Did the NATO Really Promise Not to Expand Eastward?’ the following cynical remark was made:

“Whatever American or German or other diplomats might have told Gorbachev to sugar the pill of German unification is legally irrelevant if it was not included in the Two Plus Four Treaty. This treaty does include an agreement of not stationing foreign troops and nuclear weapons in former East Germany, but says nothing about other countries joining NATO, which would also have been contrary to the general principle of international law that sovereign states have a right to decide their own alliances. Putin continues to mention the “broken promises of 1990,” but the only promises that were legally binding (because they were written down in the treaty) concerned East Germany, and they have not been broken.”

Well, sucks for the Russians to be naïve, and to believe Baker! Technically, that might be true, but is that really all there is to that? Citing that LATimes article again, the author describes how Western countries vigorously protest that such deal was ever made, but adds: “However, hundreds of memos, meeting minutes and transcripts from U.S. archives indicate otherwise.”

In 2014, when then former Soviet president Mikhail Gorbachev marked the 25th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin wall, admitted that the expansion of NATO was not discussed at that time. Gavin E L Hall, Teaching Fellow, Political Science and International Security from the University of Strathclyde, Scotland, noted the following when describing this speech by Gorbachev in this The Conversation article:

“There was, he said, no promise not to enlarge the alliance, though in the same interview Gorbachev also stated that he thinks that enlargement was a “big mistake” and “a violation of the spirit of the statements and assurances made” in 1990.”

Such high-level negotiations, especially in very volatile and fast-changing situations, do rely on diplomacy and mutual understanding, even if a lot of that understanding and diplomacy never gets formalized into an official, signed treaty. Even Gorbachev talks about the ‘spirit of the statements and assurances made’, which forms the important framework within which decisions and concessions were made, and minds where changed. To reject the importance of such an assurance, simply because it was later dropped by Baker (as George H.W. Bush was absolutely against it!), and didn’t make it into an official treaty, is untenable.

Archived transcripts of that 1990 meeting between Secretary of State James Baker and Soviet president Gorbatchev show the following:

“And the last point. NATO is the mechanism for securing the U.S. presence in Europe. If NATO is liquidated, there will be no such mechanism in Europe. We understand that not only for the Soviet Union but for other European countries as well it is important to have guarantees that if the United States keeps its presence in Germany within the framework of NATO, not an inch of NATO’s present military jurisdiction will spread in an eastern direction.”

Some claim this promise or guarantee only talks about East Germany, but a prior meeting between (West) German Minister for Foreign Affairs Hans-Dietrich Genscher in talks with British Foreign Minister Douglas Hurd on February 6, 1990, based on another set of archived transcripts, show that what was on the mind of the diplomats and leaders, wrangling with the question on how to guide this massive change into peaceful solutions. He clearly stated: “the Russians must have some assurance that if, for example, the Polish Government left the Warsaw Pact one day, they would not join NATO the next.” It shows, beyond any doubt, that Western leaders were very well aware of the optics and pressure of a NATO expansion eastwards, and how that was something unacceptable to the Soviets.

Mary Sarotte, a post-Cold War historian, points out in an interview on NPR that afterwards, a residual bitterness stayed with the Russians.

Then, in 1990, the unthinkable happens. After the Soviet Union lost control over several republics, and after a failed coup attempt, famously resisted by Boris Yeltsin from atop a tank, the red flag with hammer and sickle of the USSR was hoisted for the last time above the Kremlin, and on January 1st, 1992, the Soviet Union no longer existed. The West ‘won’. Suddenly, the United States was the only superpower, in what was now, de facto, a politically and militarily uni-polar world.

During that same interview, NPR journalist Becky Sullivan stated:

“So in 1991, the Soviet Union collapses, the Warsaw Pact is gone and all of these states that were either a part of the Soviet Union or under their influence are starting to look toward the West. And the U.S. thinks that expanding NATO is a good idea, a good way to make sure that the West still controls influence in this, like, post-Soviet Europe. The Russians, of course, are, like, very opposed to this. In their view, NATO is a threat to Russian security.

But NATO expands anyway - so first in the '90s with a few countries in central Europe, again in the 2000s to bring in even more countries further to the east, including a handful of former Soviet republics. And the Russians are just feeling more and more antagonized every time.”

In another piece by NPR’s Sullivan, James Goldgeier, an American University professor who has written extensively about NATO, explained the following:

““They [Eastern Block countries] believed that the United States could bring them into the West, which was what they wanted. And they believed that the United States could protect them if Russia ever became aggressive again.”

[Sullivan writing] From the beginning, Russia strongly objected to NATO’s borders creeping closer to its territory. In 1997, Russian President Boris Yeltsin tried to secure a guarantee from President Bill Clinton that NATO would not add any former Soviet republics. Clinton refused.

Over the course of the 1990s and early 2000s, NATO expanded three times: first to add the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland; then seven more countries even farther east, including the former Soviet republics of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania; and finally with Albania and Croatia in 2009.

“Obviously, the more it did to stabilize the situation in central and Eastern Europe and bring them into the West, the more it antagonized the Russians,” Goldgeier said.

From that LATimes article:

“Leaders in Moscow, however, tell a different story. For them, Russia is the aggrieved party. They claim the United States has failed to uphold a promise that NATO would not expand into Eastern Europe, a deal made during the 1990 negotiations between the West and the Soviet Union over German unification. In this view, Russia is being forced to forestall NATO’s eastward march as a matter of self-defense.”

Keep that in mind, as we continue our look at history.

IN 1997, Zbigniew Brzezinski, counselor to President Lyndon B. Johnson and as the National Security Advisor to President Jimmy Carter and very influential on US foreign policy, wrote one of his major works on geostrategy and geopolitics, ‘The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and Its Geostrategic Imperatives’. (Available online for free, no surprise, at the CIA website here.)

He admitted, at that early time, that Western policy makers realized that the earlier verbal promise to the Russians had to go: “Given the growing consensus regarding the desirability of admitting the nations of Central Europe into both the EU and NATO...” On Ukraine, he stated: “Ukraine, a new and important space on the Eurasian chessboard, is a geopolitical pivot because its very existence as an independent country helps to transform Russia. Without Ukraine, Russia ceases to be a Eurasian empire.”

He describes the importance of Europe and NATO to the US, in very clear terms:

“But first of all, Europe is America's essential geopolitical bridgehead on the Eurasian continent. America's geostrategic stake in Europe is enormous. Unlike America's links with Japan, the Atlantic alliance entrenches American political influence and military power directly on the Eurasian mainland. At this stage of American-European relations, with the allied European nations still highly dependent on U.S. security protection, any expansion in the scope of Europe becomes automatically an expansion in the scope of direct U.S. influence as well.”

Here we see the shift: after the fall of the Soviet Union, NATO had lost its raison d’ être. Some politicians, such as Mitterand, realized that, logically, NATO had to disappear. Yet the military structures of NATO were too useful for American projection of power and influence.

Brzezinski continues:

“The loss of Ukraine was geopolitically pivotal, for it drastically limited Russia's geostrategic options.” And he offers a great insight, that is lost on most people in the West: “Is Russia a national state, based on purely Russian ethnicity, or is Russia by definition something more (as Britain is more than England) and hence destined to be an imperial state? What are -- historically, strategically, and ethnically -the proper frontiers of Russia? Should the independent Ukraine be viewed as a temporary aberration when assessed in such historic, strategic, and ethnic terms? (Many Russians are inclined to feel that way.) To be a Russian, does one have to be ethnically a Russian ("Russkyi"), or can one be a Russian politically but not ethnically (that is, be a "Rossyanin" -- the equivalent to "British" but not to "English")?”

(From The Conversation: In this 1919 caricature, Ukrainians are surrounded by a Bolshevik (to the north, man with hat and red star), a Russian White Army soldier (to the east, with Russian eagle flag and a short whip), and to the west a Polish soldier, a Hungarian (in pink uniform) and two Romanian soldiers. Wikimedia Commons. This old image captures the different modern claimants and competitors to [parts of] Ukrainian land. Historical memory is an interesting phenomenon, let’s look at what really happened.)

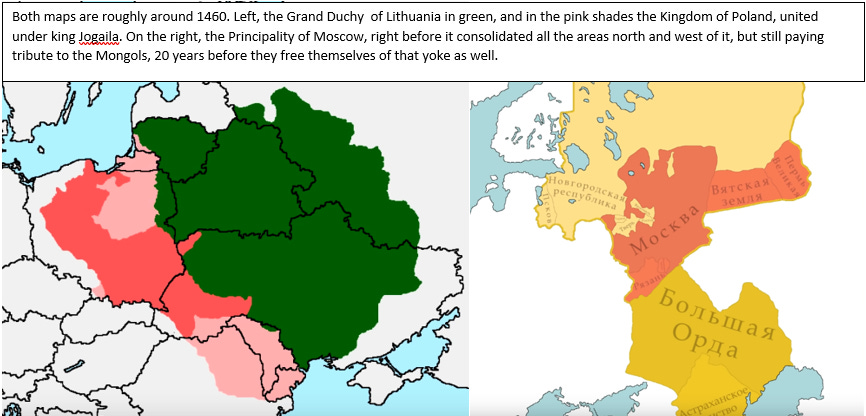

Based on my study of history, one can indeed say that Ukraine and Russia are cut from the same cloth, and are, at least, ‘brethren’, very closely related. But during the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance the territories of Kievan Rus (the name itself combines both) were divided: after the Mongol invasion in 1223 a.D. the north remained under control of the Mongols. The northern ‘Rus’ had to pay tribute to the Khans in the East, but retained some form of control, and the Russian Orthodox Church managed to flourish. Without strong oversight, the fractured domains jockeyed for power, a process that was crowned by the emergence of the principality of Moscow. When Moscow managed to reunite the Rus and consolidate their control, most significantly annexing the Novgorod Republic in 1478, the overthrowing of the Mongols didn’t wait very long, an became a fact in 1480 with the Russian victory over the Mongols at the ‘Great Stand on the Ugra River’.

After that same Mongol invasion had devastated the Grand-Duchy of Lithuania, it was never fully incorporated into the Mongol Empire, and Lithuania kept expanding, gobbling up parts of what is now Belarus in the 1250s, until by 1362 under king Algirdas the central portion of current day Ukraine was liberated from the Mongols. When his son, Jogaila, married Queen Jadwiga of Poland, the foundation for the Catholic Polish-Lithuanian union was formed.

Maps. Notice how the 4 Oblasts that joined Russia, as well as Crimea, were never part of the political entity from which Ukraine came.

Here is the seed of the disunity. While the northern Rus remained Orthodox, and under Mongol control for a good while, the southern Rus by the mid-14th century became under the Catholic Polish-Lithuanian rule. The Polish nobility was very harsh in their dealing with their ‘serfs’, which lead to numerous uprisings and troubles, including in the mid-17th century, when in 1649 the Cossack Hetmanate was founded, under Cossack leader Boghdan Khmelnytskyi (known and reviled by Jews and Poles alike as Chmiel), in a reaction against suppression by the Polish nobility, demanding more freedoms and rights. Realizing they could not beat the very powerful Polish-Lithuanian armies, the Cossacks approached the Russian Czars, and with the Treaty of Pereyaslav of 1654 swore allegiance to the Russian Csar Aleksey Mikhaylovich, effectively becoming his vassals. This period explains the origins of the Ukrainian distrust/hatred against the Poles (and the Jews).

The later history under the Czars, and most notably their experiences under the Soviets, with a very violent chapter in WWII where the Nazi’s exploited the simmering emotions, armed the Ukrainian Waffen SS division Galicia, and let them loose on Poles, Russians and Jews alike), explain the origin of their distrust and hatred of the Russians, despite the very close historic, ethnic and linguistic kinship between both peoples. 9 years of open acceptance of Neo-Nazi thought and glorification of people like Stepan Bandera and such has cemented that hatred against Poles, Russians and Jews, and allowed it to spread throughout the country.

(1943 propaganda poster: If he wants to live, he must fight, and whoever does not want to resist in this world of eternal struggle – he does not deserve the right to life. - ADOLF HITLER - The Galician SS are going into battle!)

One last important element, that absolutely contributed to the modern idea of Ukraine: the Holodomor. This is a famine that happened in the 1930s. Everyone accepts that the the cause of this deadly famine was man-made, but the intent behind it is hotly contested. Wiki gives a succinct summary: “Some historians conclude that the famine was planned and exacerbated by Joseph Stalin in order to eliminate a Ukrainian independence movement. Others suggest that the famine arose because of rapid Soviet industrialisation and collectivization of agriculture.” In the early 1990s, a national myth was needed to unify the country, against the Soviets, to justify and exemplify the desire to break away, and to strengthen the ‘national unity’ of this young new state. Talk about a shared hardship, against a common enemy, to create a sense of ‘togetherness’. Works very well. This horrible famine was a great candidate: recent enough that people heard stories from grandparents, but far enough in time to have no real living memories. And with a clear villain: Stalin and the USSR.

When I first saw the following map, I realized that what I thought I knew about the Holodomor was informed by skilled propaganda I had read growing up in the anti-Soviet and anti-Russian West: If this was really aimed against Ukraine, how come the West of Ukraine did not see much of the famine, and how come Russian Crimea and Krasnodar Krai, Rostov Oblast and Stavropol Krai similarly heavy hit with a population decline of over 20, in Krasnodar over 25%, on par with the worst parts of Ukraine? Meanwhile, the Soviets DID plan forced collectivization, were not afraid of mass murder, did practice displacing of whole peoples and ethnic groups… Where is the truth?

Everyone loves a good villain, and if you can put your own new nation against a known bad guy of the stature of a Joseph Stalin, it is easy to get the sympathy vote and the badge of honor that ‘Stalin tried, but did not manage to get us!’ As far as I can tell, there are elements of malice in some of the decisions and policies, when Stalin tried to force the Ukrainian serfs into the new demands for production, and had to deal with the different Cossack groups (also strongly present in Krasnodar Krai, having been resettled there in the late 1700s by Tsaristic Russia to strengthen the border there), yet I still think the main culprit is simply the stupidity of thinking the Communists could dictate whole economies from above, without any consideration of the local realities, where the repression was the by-product of Soviets trying to sweep this failure under the rug, not the driving reason of a ‘planned genocide’ against this or that ethnic group.

It is no coincidence that this famine coincided with the implementation of the first ‘five year plan’, that had started in 1928, and mandated farmers to work together in massive kolkhozes. When the production targets of grain fell behind with more than 30%, the USSR still demanded the grain be sent for redistribution among the whole Union, leaving the farmers without their own crops, increasing the feeling they were targeted. The forced silence on this absolute debacle did not help appease any suspicion by the people within Ukraine that the famine was linked to a targeted campaign of revenge and submission. Meanwhile, this was all part of ‘dekulakization’, a policy targeting ‘Kulaks’: "peasants with a couple of cows or five or six acres [~2 ha] more than their neighbors" and were labeled ‘class enemies of the Soviet Union’. A typical story of forced redistribution and collectivization gone horribly wrong. Who could have foreseen that, really?

(A parade under the banners "We will liquidate the kulaks as a class" and "All to the struggle against the wreckers of agriculture", Wikipedia)

Which does not justify the massive deaths that were directly caused by human intervention and force, at all! Wherever the truth lies, pure genocide or soviet failure of collectivization, it did have the effect of unifying a shared identity as ‘Ukrainians/Cossacks’ against the Soviet Union, which was strongly identified with ‘the Russians’. Today, as cannot be dismissed by whatever version of the Holodomor you hold to, the memory of that period serves both as a cause for unity within Ukraine, as well as the ground for a strong hatred, distrust and enmity against the Russians, as heirs of the Soviets.

Back to the 21st Century.

In the previously mentioned article by Gavin Hall, he pointed out that “Russia also demonstrated its continued to desire to remain in a cooperative security relationship by developing the Nato-Russia Council in 2002”, yet maintains that “Russia gave at least tacit approval to the enlargement, including the former Soviet Baltic states, and was signalling its desire to be a partner in the European security architecture.” And he concludes “it can be argued that Nato is not an aggressive, expansionist alliance”.

Russia can still want to be a partner for European Security and work with NATO, and ALSO strongly object to further expansion.

This tweet from the official NATO account on Twitter shows how the reach of NATO missions and involvement is reaching well beyond EU borders, let alone European borders.

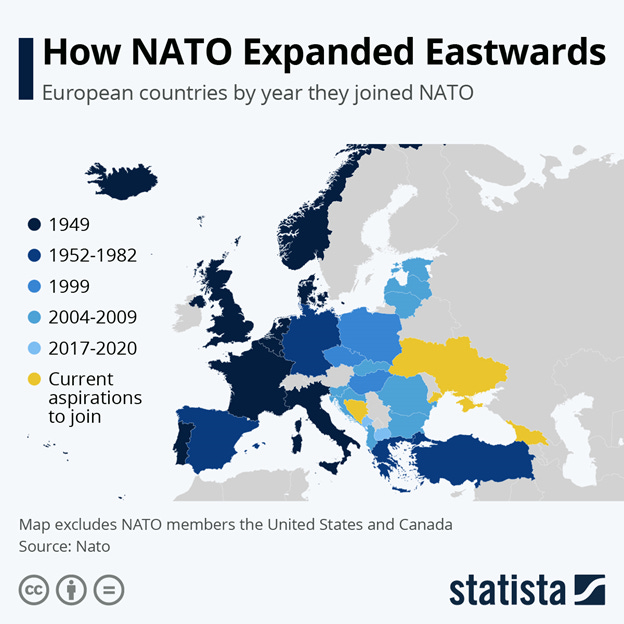

And this map also speaks volumes (keep in mind that Finland and Sweden were supposed to join very recently, but opposition of Turkey that escalated prevented that: the border of NATO in the north is also right up to Russia):

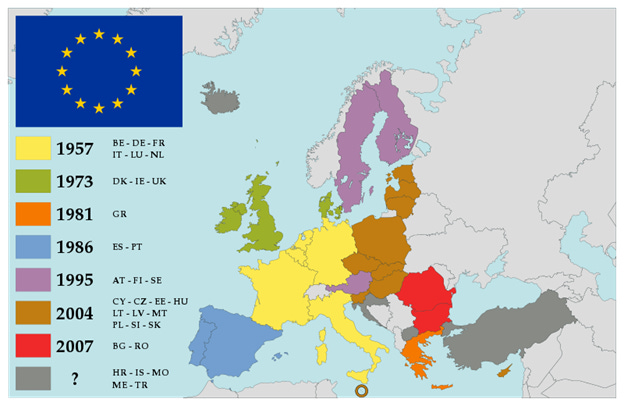

In this context, consider also this expansion map:

In 1999, the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland joined NATO. In 2004, Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Slovakia, and Slovenia were added, creeping ever closer. Next, in 2009, Albania and Croatia, Montenegro in 2017, and North Macedonia in 2020, joined the ranks of NATO. Sweden’s membership is in chaos now, with the veto by Turkey, amidst effigies of Turkish president Erdogan being hung up in Stockholm, and the burning of Qurans during Swedish protests, and that of Finland also uncertain.

Meanwhile, the EU expanded in 1995, with Austria, Sweden and Finland, and then, also in 2004 (May 1), Cyprus, Malta, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia, Latvia, Estonia, Lithuania, Czech Republic, and Slovenia. In 2007, Romania and Bulgaria joined the EU, and in 2013, Croatia. Membership for North Macedonia, Montenegro, Albania and Serbia are in negotiation (negotiation with Turkey are frozen); Ukraine, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Moldova are candidates, and Georgia and Kosovo are applicants.

In a 1998 paper by Lt. Col. James M Milano for the Strategy Research Project, title “Nato Enlargement From the Russian Perspective”, we get a reflection of how Russia responded, seen through the eyes of a contemporary:

“In the opinion of many of the Russian policy elite, media, academic institutions and military, NATO has served its purpose and, with the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact, can claim no bona fide justification for its continued existence.”

Tellingly:

“Russia has diplomatically contested the enlargement of NATO since discussions concerning the issue began in 1992. There are many reasons for Russia's concern and at times visceral opposition to NATO enlargement, and this paper will explore these reasons.”

The article contains some other nuggets of insight, observation and a reflection of Western perception in the 90s on this topic, worth a read.

The same happened around the 2004 additions to NATO ranks. An April 3, 2004 article of the NYTimes sketches this view: “The fighter jets that landed this week at the airfield northwest of here do not pose much of a threat, but their arrival at what was once one of the Soviet Union's largest bases underlined in bold the new borders being drawn between Europe and Russia.”

The author captures reality well, with this phrase: “While Russia has resigned itself to NATO's expansion, albeit grudgingly …” Yes, Russia did not escalate things, nor put up red lines or other ultimatums, but did all it could to cooperate and make things work, while never leaving their complaints fully behind (remember this, this will come back up in a later article). “The operation is purely defensive, NATO officials and military commanders here say.” Yes, as we all know, troops and armies and rockets and weapons and tanks and fighter jets are purely defensive. Until that split second the decision is made and the order is received to attack. Preventive, of course, only to be seen and understood as an extension of their original ‘defensive posture’.

And in another NYTimes article, Putin is cited from a televised appearance with then NATO Secretary General Jaap de Hoop Scheffer, saying ''Russia's position toward the enlargement of NATO is well known and has not changed.”

Further evidence is a March 10, 2006 report by the Council on Foreign Relations, that makes the claim that ‘Russia is on the wrong direction’. Why? Among other things, because “In 2005, Russian officials sought to curtail access by the United States and NATO to Central Asian air bases.” They note themselves that Russians started to act based on their own geopolitical concerns, and started to act, together with China, to counter or reverse the growing American presence in the Region (something the CFR authors readily admit was/is happening).

Next, in 2008, NATO met at the Bucharest meeting, and invited Putin at the table, as membership for Ukraine (and Georgia) and other topics were discussed (such as the placement of missile defense systems in Poland and the Czech Republic). At the end, a declaration was issued by NATO.

Both concerns for Russia were ignored.

“NATO welcomes Ukraine’s and Georgia’s Euro Atlantic aspirations for membership in NATO. We agreed today that these countries will become members of NATO. Both nations have made valuable contributions to Alliance operations. We welcome the democratic reforms in Ukraine and Georgia and look forward to free and fair parliamentary elections in Georgia in May. MAP is the next step for Ukraine and Georgia on their direct way to membership. Today we make clear that we support these countries’ applications for MAP. Therefore we will now begin a period of intensive engagement with both at a high political level to address the questions still outstanding pertaining to their MAP applications.”

Meaning: even though there were protests (including France and Germany, not just Russia), Georgia and Ukraine will continue to be on the path towards membership, we just won’t decide right now about offering them a MAP (Membership Action Plan, the process on how to become a member), but we’ll decide later. That would give them time to smooth things over with France and Germany, but the Russian concerns were deemed irrelevant, not taken into account by keeping that door open, and actively continuing towards that goal.

“We reaffirm to Russia that NATO’s Open Door policy and current, as well as any future, NATO Missile Defence efforts are intended to better address the security challenges we all face, and reiterate that, far from posing a threat to our relationship, they offer opportunities to deepen levels of cooperation and stability.”

More nonsense: well, it’s just a bona-fide effort to address security challenges, ones we ALL face, so they are no threat, but a chance to work closer together! Meaning: we will just do whatever we want, and you can pout about it, or accept it and ‘work with us’. Nice wording, aimed to isolate Russia as ‘unwilling to cooperate on vital security challenges’ in case they kept up their protest.

Putin’s reaction to Bucharest Declaration, as reported by ABC Australia: “the presence of a powerful military bloc on Russia's borders would be seen as a direct threat and […] assurances that it is not could not satisfy his country.”

And as Prof. Mearsheimer explained in a lecture on Ukraine, “Moscow complained bitterly from the start [about NATO expansion]. During NATO’s 1995 bombing campaign against the Bosnian Serbs, for example, Russian President Boris Yeltsin said, “This is the first sign of what could happen when NATO comes right up to the Russian Federation’s borders. … The flame of war could burst out across the whole of Europe.””

This is nothing new, and Russia has been clear about this from the beginning.

Why do I spend so much time and detail on this?

Because ever since February 2022, a revisionist effort is made to downplay the role of the NATO (and thus, the US) in the current war in Ukraine, to put Russia and Putin in as bad a light as possible.

I will give one example, from the Center for International Security and Cooperation (original here), as republished by the Brookings Institute. It is an Op-Ed, empathically titled ‘One. More. Time. It’s not about NATO’. The subtitle does not mince words: “Vladimir Putin and the Kremlin had a number of reasons for invading Ukraine in February and starting the largest military conflict in Europe since World War II. Putin sought to portray the pre-invasion crisis that Moscow created with Ukraine as a NATO-Russia dispute, but that framing does not stand up to serious scrutiny.”

It takes about how Putin ‘suddenly’ started to talk about grievances, including how the US and NATO did not want to give assurances they would not expand NATO, beginning in late 2021 (which means, as they want us to believe, that Putin did this in the immediate run-up to the war, which started Feb 2022). It added some other examples, namely “along with false claims of neo-Nazis in Kyiv, genocide in Donbas and a Ukrainian pursuit of nuclear arms”. This shows that this article is pure propaganda, designed to provide cover for the Western countries, US first, in this conflict. The War for our Minds is real.

Where to even begin to answer this?

False claims of neo-Nazis in Kiev? The evidence is all over, as I have chronicled, as is the introduction of books glorifying Stepan Bandera and other Nazi collaborators who perpetrated mass murder and other crimes as a very clear systemic proof of the resurgence of the Nazi ideology, in whatever way it has changed to allow people like this to claim there is no real ‘neo-Nazism’ in present day Ukraine.

Genocide in Donbas? The use of petal mines (that Western media wants to blame on the Russians, but why would Russia spread mines over the territory they themselves are holding?), the targeting of civilian areas in Lugansk and Donetsk Oblasts, the rounding up of civilians who accepted food packets from Russian troops (this even was passed as an official law/rule from Kiev, in violation of Geneva!), etc., all point to that unsavory fact, that Kiev doesn’t mind to use such ‘final solution’ to clear up Ukraine and get rid of those pesky Russian speaking Ukrainians who voted wrong and dare protest when the president they voted in gets ousted in a coup.

And Ukrainian pursuit of nuclear arms? On February 19 Zelensky started talking about Ukraine's withdrawal from the Budapest Memorandum and suggested the possibility of acquiring its nuclear weapons (see this article, and Zelensky’s full speech here). This was BEFORE the Russians invaded!

On February 25 Jean-Yves Le Drian (French Foreign Minister) said, as reported by Reuters: "Vladimir Putin must understand that the Atlantic Alliance is a nuclear alliance." At this point, one day after the start of the Russian invasion, there was no direct threat to NATO. But there have been many talks about making Ukraine part of NATO. What was the suggestion here?

Jaroslaw Kaczynski, the Deputy Prime Minister of Poland, added his voice on April 3, as reported by The Times: "If the Americans asked us to place nuclear weapons in Poland, we would be open to it. It would significantly strengthen Moscow's deterrence".

On April 16, 2021 (again, a full year BEFORE the invasion started), Andriy Melnyk, Ukraine’s ambassador to Germany, warned in an interview with a German radio station that “Kyiv may be forced to acquire nuclear weapons to safeguard the country’s security if NATO does not accede to its membership demand amid spiralling tensions with neighbouring Russia.”

This goes back much further, and already in 2014, Rizanenko, a member of the Udar Party, said to USA TODAY “Ukraine may have to arm itself with nuclear weapons if the United States and other world powers refuse to enforce a security pact that obligates them to reverse the Moscow-backed takeover of Crimea.” And he added that this pact was "to assure Ukraine's territorial integrity". (Funny thing: When Ted Cruz said that Ukraine gave up their nukes in the 1990s because the US had said it would ensure Ukraine’s territorial integrity from Russia, PolitiFact rated that ‘False’…)

Now, are those credible indicators of a real and achievable plan to obtain nukes? Isn’t this just blackmail, grandstanding, by a desperate Ukrainian government (as Cato Institute surmised in their article)? It most likely is, but even as such, Ukraine DID bring up the nuclear pursuit, and as such, it is not a false claim, even if the truth and reality is that even if Kiev did decide to build or acquire nukes, it more than likely would fail well before they could get started.

And on Putin blaming NATO falsely for continuing their expansion despite promises not to? The article brings up a series of arguments that talk about degree, not about principle. “NATO only places limited amounts of troops on the territory of the new states”, they say, as if that limited number makes it ok for Russia, and as if a small number today could not very easily pave the way (literally and figuratively), for a much larger force tomorrow? They wrote that statements by NATO about ‘not placing nuclear weapons’ in those new member states, or about ‘permanent stationing of combat troops’, “reflected the Alliance’s effort to make enlargement for Moscow as non-threatening as possible in military terms.”

Russia understood that those are empty promises. A small force can easily prepare a base for a much larger one. Combat forces can be brought in quickly with todays transportation means. And things like missile defense systems could pose a much bigger initial threat. Reuters reported as early as November 12, 2012, that “Washington already rotates a Patriot missile battery through Poland, one of its most loyal NATO allies.” Having such types of defensive capabilities would be the exact shield under which to quickly bring in those combat troops into the new member states, defending it from counter-fire from Russian planes and rockets.

2004 also sees the first ‘color revolution’ in Ukraine, the so-called Orange Revolution. Without going into too much detail, apart from mentioning that it was an electoral battle over the presidency between pro-Russian Yanukovich and pro-Western Yushchenko (who would win after the courts ordered a new election), sources are divided: some claim there was no US involvement, others see very clearly an American hand in this ‘promotion of democracy’. Even The Guardian headlines in November 2004, in the midst of this coup, that there is a “US campaign behind the turmoil in Kiev”. In a scholarly study, titled “The Orange Revolution: ‘People’s Revolution’ or Revolutionary Coup?”, Prof. David Lane (Emeritus Fellow of Emmanuel College, Cambridge University, UK, prof. Sociology, who wrote widely on state socialist societies, the USSR, Marxism, elites, class and social stratification) wrote “Based on public opinion poll data and responses from focus groups, the author contends that what began as an orchestrated protest against election fraud developed into a novel type of political activity—a revolutionary coup d’état. It is contended that the movement was divisive rather than integrative and did not enjoy widespread popular support.” What he found, points to Astro-turf, not to a real, organic movement. And this, in turn, lends a lot more credence to the side who sees a Western Coup in this 2004 Orange Revolution.

‘The Guardian’, not a Media outlet that can be accused of being a Moscow propagandist, saw it the same, at that moment (they might have been ‘coaxed’ into lockstep with the narrative later, but this is their assessment at the time itself):

”But while the gains of the orange-bedecked "chestnut revolution" are Ukraine's, the campaign is an American creation, a sophisticated and brilliantly conceived exercise in western branding and mass marketing that, in four countries in four years, has been used to try to salvage rigged elections and topple unsavoury regimes.”

Fast forward to the end of 2013, new presidential elections in Ukraine, where Viktor Yanukovych was again candidate, this time as the incumbent, against Yulia Tymoshenko. Instead of going into detail, which is necessary, but would take too long, see my previous background article ‘The War in Ukraine: Europe’s meddling - An overview of the Ukraine crisis, and the central role of the EU, aided by the US’. If you haven’t read that one yet, make sure to read that next, as it provides a lot of important detail that will create a much clearer picture.

In short, the president of Ukraine in 2014, Viktor Yanukovych, was in negotiations with the EU about EU membership, and the signing by Ukraine of an ‘Association Agreement’ to commit to take the steps to join the EU. The financial requirements were steep, and Yanukovych asked the Russians if they could lend him the money needed to implement the necessary reforms and measures to qualify. Russia declined, telling him that if he wanted to go the EU, he could, but that Russia would not pay Ukraine so they could sever economic ties with Russia. Yanukovych then faltered in his support for Ukraine’s EU membership (also coming up close to reelections), and those negotiations were put on halt.

As Cato Institute wrote in their article ‘America’s Ukraine Hypocrisy’, “the extent of the Obama administration’s meddling in Ukraine’s politics was breathtaking”:

“Instead, U.S. officials were blatantly meddling in Ukraine. Such conduct was utterly improper. The United States had no right to try to orchestrate political outcomes in another country—especially one on the border of another great power. It is no wonder that Russia reacted badly to the unconstitutional ouster of an elected, pro‐Russian government—an ouster that occurred not only with Washington’s blessing, but apparently with its assistance.”

This sketches the background. Most people have no idea, or heard about aspects of this, but don’t know how to put it all together.

Russia’s reaction was taken based on this long ranging as well immediate history.

In the next article, we will look closer at the immediate aftermath of 2014, the first ‘invasion’ of Russia in to Ukraine, when they annexed Crimea, all the way up to their second invasion of the Special Military Operation that began on February 24, 2022. In those 9 something years, a lot has happened, and a lot has changed, including Russia’s stance and goals. It is vital to look at those details, to better understand why we are where we’re at.

So excellent and concise I have saved it to a special folder as ammunition next time I come up against arguments about NATO expansion.

Excellent work.